During the hours between midnight and dawn on Sunday, March 11, 2012, local time (March 10, U.S. time), American troop(s) – one, according to non-eyewitnesses, more than one, according to most eyewitnesses – who’d been deployed, pursuant to the September, 2001 Congressional Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), at a small Forward Operating Base (FOB) [or Combat Outpost (COP; aerial photo, added 12/12/12)] named Camp Belamby – reportedly a “U.S. special-operations forces base” – in Panjwai district, Kandahar province, southern Afghanistan, barbarically shot and killed at least 16 unarmed civilians – 9 8-10 children (six of them under Age 10), 4 4-5 women, and 3 4-7 men – in their homes and beds in two (or three) two-three, or more, nearby settlements, and wounded at least 7 others, including 5 more children.

With most families in that rural farming region of Panjwai apparently too poor even to afford guns, the only defenses those Afghan citizens had against the overwhelming force of their attacker(s) were their barking dogs; those dogs – according to two different accounts apparently originating in separate villages (one to BBC News from an unnamed woman in “Najeeban,” and one to Australian SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim from a wounded girl [Noorbinak, reportedly of Alkozai] who lost her father) – were the first creatures shot and killed by the heavily-armed attacker(s) that night. Attacker(s) who apparently didn’t face returning fire from even a single gun fired in self-defense by the terrorized villagers – who’ve been repeatedly subjected over the years to General Warrant-style entry-at-will into their homes by armed foreigners – targeted in either 2-3, or more, rural settlements clustered along narrow dirt lanes bordering wheat fields and vineyards. [“‘As we understand it, the special forces have the power to do whatever they want, such as conducting operations and arresting people,’ (Haji Mohammad) Noor (head of the Panjwayi district council) said.”]

Since then, as Senior Al Jazeera Producer Qais Azimy put it in a blog post on Monday, March 19:

Many mainstream media outlets channelled a significant amount of energy into uncovering the slightest detail about the accused soldier – now identified as [non-special-forces Army] Staff Sergeant Robert Bales. We even know where his wife wanted to go for vacation, or what she said on her personal blog.

But the victims became a footnote, an anonymous footnote. Just the number 16. No one bothered to ask their ages, their hobbies, their aspirations. Worst of all, no one bothered to ask their names.

In honoring their memory, I write their names below, and the little we know about them: that nine of them were children, three [or four, or five] were women.

Or, as an Everett, Washington commenter named “Filbert” put it 3/25 on the website of the Seattle Times, in response to the paper’s publication of an important March 24 Associated Press article about the victims: “Seattle Times, why do stories of Bales get plastered all over page 1 for 2 weeks, and when you finally get around to it, the story of this man [Mohammad Wazir of Balandi/Najiban, who lost 11 members of his family] is relegated to page A14?”

Azimy’s list – replicated at the foot of this post – does indeed seem to be the most comprehensive English-language account to date of the names of the killed and wounded in these small, close-knit farming communities. The U.S. government’s March 23, 2012 military Charge Sheet for Staff Sergeant Bales lists no ages for those killed, redacts all the names of the victims, and lists no name for the unknown 17th victim, evidently a female; yet the victims were apparently well-enough known to the U.S. military by Saturday, March 24 for surviving family members to receive some monetary compensation (“The families of the dead, who received the money Saturday at the governor’s office, were told that the money came from U.S. President Barack Obama, said Kandahar provincial council member Agha Lalai”). The hurried early reporting does include scattered accounts of names and ages of some of the victims, but often confuses or omits their names and/or villages; their villages are likewise not specified by Azimy, nor included in the U.S. Charge Sheet. Only after Azimy’s 3/19 post was published did some more detailed and valuable English-language reporting about the victims begin to fill in some of the obvious gaps in coverage (joining an early, laudable New York Times report from March 12) – in the Wall Street Journal on March 22, at GlobalPost.com late March 22/early March 23, [in BusinessWeek March 22/23 {the BusinessWeek URL was later changed to BloombergBusiness}, including important information about a Najiban eyewitness, which I belatedly found and excerpted at the end of my follow-up July 7th post,] in the Associated Press on March 24, and in a humane opinion piece – “Are all innocent victims equal?” – by India/Kabul-based CNN International correspondent Sara Sidner, who took the time to include the names of all 16 killed (her source was Afghan officials, and her list matches the Qais Azimy list below, aside from regional differences in spelling and address).

Sara Sidner’s March 24 opinion piece compassionately echoes and reinforces Azimy’s:

These are the names of the men, women and children allegedly murdered by a U.S. soldier in Afghanistan’s Panjwai District in Kandahar Province on March 11, according to Afghan officials. The U.S. military has now added one more name to that list but no one has revealed that victim’s name so far.

In this case, the how was quickly explained by witnesses, village elders, Afghan and NATO officials: They were shot dead. But looking across local, regional and international media for days after the massacre the full list of names and ages was nowhere to be found.

Even when some of the family members of the victims and village elders came to Kabul to the presidential palace to speak with President Karzai [on Friday, March 16], few started by announcing their names but instead launched into accounts of what happened that night. And even they were at a loss to name every single victim at the time.

[…]

Also there is no real “digital footprint” in villages where electricity and running water are luxuries, making communication extremely difficult.

Ages were often hard to ascertain, because, like many places in the world with poverty and high illiteracy rates, people do not know their birth dates.

[…]

Life is not cheap. It never was and never will be — no matter where you live. I have witnessed the suffering of a mother in Oakland, California, whose child was killed by a bullet and the grieving of a mother in Sukur, Pakistan, whose child was swept away by a flood. There is no difference in the amount of pain they endure, or the tears they shed.

So in the interest of innocent victims everywhere, we as journalists need to work harder to find out who they were, to paint a picture of the lives they had and the people who grieve for them.

May they all rest in peace — and be counted.

To its great credit, in late March the Australian public television network SBS added to those valuable print reports (and to the invaluable early photographs and video footage obtained by Afghan reporters) some extremely helpful, difficult-to-obtain television footage – of interviews with some of the surviving relatives of those killed that night, and of one of the homes in one of the villages where people were killed – taken during a trip to Panjwai by Australian SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim and cameraman Ryan Sheridan for this March 27, 2012 SBS Dateline program (the main source of the multiple screen-captured images in this post):

Because of its sensationalism, among other, higher motives we can hope, many non-Afghan media outlets paired with local Afghan reporters to have at least one go at this story – a real “Saturday Night Massacre” committed by someone(s) serving in the Executive Branch of our government. The resulting coverage, as hasty and heavily Pentagon-tilted as it is, remains a valuable record, even though it primarily consists – once the many press-release pronouncements from nominally-responsible authorities are removed – of a muddled and unnecessarily confusing scattershot of information, which has been given little follow-up. To date, no non-Afghan account that I’ve seen has tried to systematically list, by location, name, relationship, and age, the 4-5 6 (or more) households primarily affected by the killer(s) that night, or to put faces to the foreign names for English-speaking audiences.

Nevertheless – in spite of the attempt by at least one American media outlet [print page “no longer available” 10/8; replacement link] to place blame for the confused reporting on the traumatized and grieving victims themselves, and the efforts of many in the media to imply that the real story is now shrouded in mystery or unobtainable, in the face of heavy Pentagon/NATO/ISAF pressure to toe the U.S. military’s “lone gunman” line on the attacks – when the scattered (and, obviously, translated, however imperfectly) snippets in media reports quoting Afghan witnesses and survivors are organized and examined, the accounts by the Afghan villagers seem to be remarkably consistent and coherent.

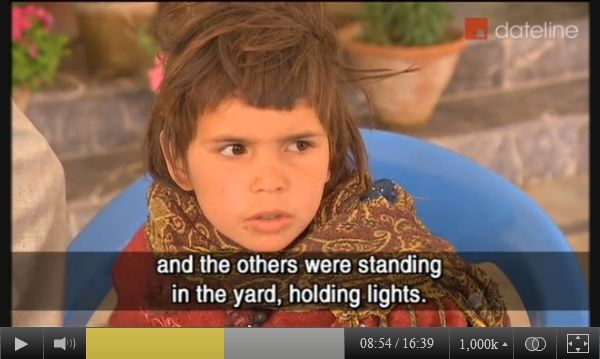

Notably, those accounts by Afghan villagers – in non-Afghan media outlets, though apparently mostly obtained by local, on-the-ground Afghan reporters – who witnessed the attacks, and/or their aftermath, provide very little corroboration from named Afghans describing a lone U.S. soldier as responsible. This is true even though more than one named survivor (three of them children) describes being shot at by a single (unidentified American, or “NATO,” in one case) soldier – because that single soldier is also generally described by the same survivor, or by their family, as being accompanied by other soldiers, often carrying lights, elsewhere in the home, or in the yard between the house itself and the courtyard wall that fronts the public street – a common layout in these small settlements, as seen in this screen capture from the SBS-TV Dateline footage of Alkozai filmed on March 23, 2012:

The closest thing to named sources for the lone gunman theory, among eyewitnesses, that I’ve seen to date are the off-camera accounts of two children – family or families unnamed, but likely [or maybe not, per new information given to CNN by Yalda Hakim in an April 11 interview, as quoted in Comment 2 below] possibly from the Mohammad Naim home in Alkozai (whose wounded boy may be is known as Sediqullah, and whose wounded girl’s name I don’t know is Parmina or Parween; see Comment 13 below) – who reportedly told Yalda Hakim of the Australian TV network SBS the following, when Hakim visited the Panjwai district in late March (quoting from Hakim’s remarks in a brief interview that CNN did with Hakim after her Panjwai visit):

“Two of the children I spoke to told me that they only saw one American in their house. The [third] 8-year-old girl [Noorbinak, family name not mentioned] I spoke to [at the hospital, where she’s being treated for a leg wound] said she saw several Americans in her house.” – SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim, March 29, 2012

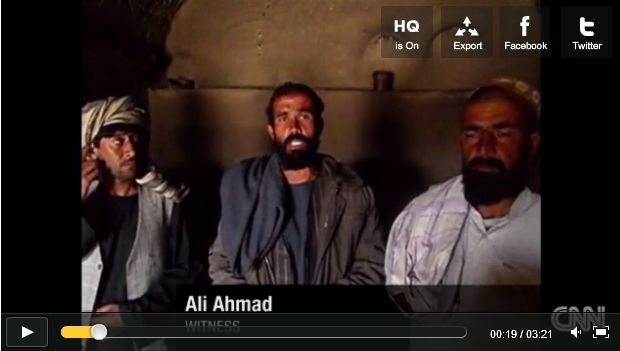

[April 27 Update: I’ve now discovered a valuable video clip aired by CNN International on March 18th or 19th, that includes brief eyewitness accounts by two unidentified boys reporting that they saw a single soldier – and who’re this time recorded on camera (apparently on or soon after March 11), as shown by the following screen capture of CNN’s NEWS STREAM broadcast. Their words, as translated and transcribed by CNN, are posted below the screen capture. (((Later information obtained from family members – see my follow-up July 7th post – revealed that one man with the boys is a nephew of Mohammad Dawood – Toor Jan, called “Ali Ahmad” by CNN – and another a brother of Dawood – Abdul Woddod – making it almost certain that the two young boys are two sons of Mohammad Dawood, who lived about 1/2 kilometer northeast of Balandi/Najiban.))) The village in which the two boys evidently witnessed the March 11 attack is not specified, but they seem to be from (near) Balandi/Najiban, which is where at least the beginning (and perhaps all) of that CNN Panjwai footage was filmed (as introduced by CNN International Correspondent Sara Sidner, and as indicated by the account of the only named, adult witness quoted on camera – see the related update in the Balandi/Najiban section below about this previously-unmentioned witness). Thus, I’m deducing that these boys are sons of Mohammad Dawood of from near Balandi/Najiban, who was murdered that night, because they are filmed standing next to the man (Ali Ahmad) who identifies Mohammad Dawood as his uncle, and because the design of the tunic or top worn by the older boy in this CNN screen capture closely matches the tunic worn by a Dawood child in the SBS-TV screen capture I included in the Balandi/Najiban section below. (Alternatively, one boy could be a Dawood son, and the other, older, boy perhaps a son of Ali Ahmad from the same Dawood home.) However, the older boy seen here (with the matching tunic) does not seem to be visible in the SBS-TV video footage of the Dawood children taken in Kandahar city in late March After further review (May 24), I crossed off that statement because I now believe that the older boy is briefly visible in the March 27 DatelineSBS footage of the Dawood children – in the right rear at about 15:51; thus, if not Ali Ahmad’s son, he may well be the seventh (and oldest?) Dawood child – if the Dawood family does indeed have 7 children instead of the 6 usually cited. (At one point in the DatelineSBS footage of the Dawood family, there do seem to be seven children present around Dawood’s widow Massouma/”Aminea.”) Also, I believe, but can’t be sure, that the younger boy in this CNN screen capture is the Dawood boy closest to the camera in the SBS screen capture included in the Balandi/Najiban section below. Assuming that these boys are two of the Dawood children, or at least both members of the extended Dawood family, the CNN footage seems to reveal an obvious conflict about the number of attackers in Balandi/Najiban the Dawood home (1/2 KM away from Balandi/Najiban) between eyewitnesses in the same family and home (which CNN didn’t recognize, or didn’t point out) – with Dawood’s widow and Dawood’s adult nephew (Ali Ahmad/Toor Jan) reporting multiple soldiers (at least in the yard), and two of the Dawood family’s children reporting one soldier (at least in the home). (Dawood’s widow seems to have made it clear to Yalda Hakim of SBS that Mohammad Dawood was killed outside the home, in their exterior courtyard, although she said that at least one soldier also entered the home itself. See the Balandi/Najiban/Dawood section below, and Comment 2.) Because Yalda Hakim visited Dawood’s relocated widow and children in Kandahar city before her March 27th SBS broadcast, one of these two eyewitness boys may well be the third, off-camera male child she mentions above and in Comment 2 below as reporting a single shooter. If so, Hakim too (despite almost certainly understanding the relationship between the Dawood family members involved) didn’t point out in two of her subsequent interviews with CNN that the off-camera account to her by one of these boys was from a child of the same family in from near Balandi/Najiban whose key adult eyewitness (Mohammad Dawood’s widow) graphically described to Hakim and others a group of soldiers in her yard (and searching her home, including her “bathroom”) when her husband was killed.]

Mohammad Dawood sons Hekmatullah 'Khan' Gul, right, and Nasibullah, left, who watched or heard their father being murdered at their home - 0.75 KM south of Camp Belamby, and about 0.50 KM east of the Mohammad Wazir home - during the Panjwai Massacre, and who say they saw or heard one soldier enter their room that night from - per Hekmatullah in October, 2012 - the 'bright as noon' courtyard outside, as recorded (without identification) in a CNN International broadcast aired March 19, 2012

Most of the villagers [interviewed in, apparently, “Najabyan” alone, including some residents of the nearby Dawood home located across a vineyard from the village] say they do not believe the U.S. version. But when it comes to actual eyewitnesses, their stories conflict. One of the young witnesses said [among other things; see the Balandi/Najiban section below], “He was an American.” “It was just one person,” the [younger] boy next to him chimes in. But some adults in the village tell us they have evidence more than one soldier was involved, but none of them have said more than one soldier was [firing] a weapon. – CNN International NEWS STREAM transcript, March 19, 2012

Volunteers at Wikipedia have added significantly to the value of the spotty, isolated reports of the individual media outlets – by obviously working hard, early on, to gather in one place the links to those various reports, and by trying to construct a coherent narrative of the March 11th attacks from them. And Marcy Wheeler did some important preliminary analysis at her blog of the reporting about the victims (which led her to ask whether different numbers of troops were involved in the northern village shootings as compared to the southern village shootings, and which highlighted, among other things, how little care the “professional” reporters and editors took to obtain the basic “who, what, when, where, why, and how” of the attacks).

This post builds on that earlier work to connect some faces to the names, and to collect, organize and highlight the solid on-the-ground reporting about eyewitness accounts (and associated early photographs of locations and victims) provided by Afghan locals working for the Associated Press and other media outlets – accounts and photos that I’ve used to add some educated guesswork of my own about victim identities to attempt to fill in some of the reporting gaps. Corrections and additions to what follows are welcome; all emphasis in quoted excerpts is added.

Access to the shooting sites and to the hospitalized survivors is evidently limited and difficult (thanks to both the Taliban – which one unnamed resident, apparently from the southernmost village, early on told BBC News hadn’t been seen in the area before the killings for five months – and to the negative-publicity-paranoid, secrecy-obsessed American government), so, as with much of what’s been done in our names in Afghanistan by our Armed Forces over the last decade, a month after the cold-blooded war-crime killings occurred, we still have few firm details and conflicting accounts about what exactly happened that night. Yet, on the one-month anniversary of the attacks, the American media’s attention – guided by the Pentagon’s energetic, if undocumented, claims abuut a lone U.S. gunman – is quickly turning elsewhere.

One of the most glaring examples of unexplained, confusing discrepancies in the reporting from Panjwai – not addressed by any media account that I’ve seen [until the update in Comment 4 below] – is that the southernmost village where killings took place (of the two-three [or more] villages located near the Camp Belamby base that were attacked that night) is being simultaneously identified (by different reporters) as both “Najiban” and “Balandi” (or by similar variants, like Najeeban and Belandi-Pul). Three separate map graphics created by different media outlets to show the location of the settlements in Panjwai district use the name “Najiban,” while some of the best early on-the-ground reporting uses “Balandi” to identify the same village.

Here’s the March 12 BBC version of the location of the Panjwai villages involved (superimposed on a Google Earth image of the terrain) – a map which appears to reverse the position of two settlements (placing “Najeeban” to the north and Alkozai to the south of the military base Camp Belamby, rather than the other way around as shown in SBS-TV’s March 27 Dateline graphic further below):

[A later BBC report – from March 17th – includes the same map, and explains the reason for the inclusion of the location “Ibrahim Khan” this way: “The soldier, who was later named as Staff Sgt Robert Bales, is said to have broken into three homes in three different locations in Panjwai district – the villages of Alkozai and Najeeban and another settlement known locally as “Ibrahim Khan Houses.” I’ve so far found no other details about that settlement – neither the names of the victims who were wounded (or killed) there, or exactly where it is in relation to Camp Belamby —> which remained the case until the Ibrahim Khan Houses neighborhood of Alkozai was later mapped by Afghan reporter Mamoon Durrani based on his March 11 visit, and described by its former resident Rafiullah in late 2012 — see my July 7, 2012 post and its 2013 updates, as well as my June 5, 2013 post and maps for more).]

The following, apparently accurate, graphic was produced by the Australian TV network SBS for its Dateline program on March 27, after its reporter had returned from visiting Alkozai and Camp Belamby [note that unlike a graphic published by GlobalPost.com on March 22, which extrapolated from a map of 3 Alkozai homes drawn for their reporter(s) by one of the eyewitness survivors of the attack in Alkozai, SBS here places one village (Alkozai) north of the military base and one village (Najiban/Balandi) south of the base – rather than placing both villages south of the camp, as GlobalPost’s graphic seems to do]:

With that as introduction, I want to highlight what seems to have been the beginning – the motivating event – for the overnight massacre of March 11th, courtesy of a very important Associated Press report by Mirwais Khan (who’s the source of other valuable on-the-ground Panjwai reporting for the AP), published Wednesday, March 21st:

[…] Villagers said the earlier [roadside] bombing occurred in Mokhoyan, a village about 500 yards (meters) east of the [Camp Belamby] base.

[…]

One Mokhoyan resident, Ahmad Shah Khan, told The Associated Press that after the bombing, U.S. soldiers and their Afghan army counterparts arrived in his village and made many of the male villagers stand against a wall.

“It looked like they were going to shoot us, and I was very afraid,” Khan said. “Then a NATO soldier said through his translator that even our children will pay for this. Now they have done it and taken their revenge.”

Neighbors of Khan gave similar accounts to the AP… […]

[…]

On March 13, Afghan soldier Abdul Salam showed an AP reporter the site of a blast that made a large crater in the road in Panjwai district of Kandahar province, where the shootings occurred. The soldier said the explosion occurred March 8. Salam said he helped gather men in the village, and that troops spoke to them, but he was not close enough to hear what they said.

[…]

“The Americans told the villagers, ‘A bomb exploded on our vehicle. … We will get revenge for this incident by killing at least 20 of your people,'” [Panjwai district tribal elder Ghulam] Rasool said. “These are the reasons why we say they took their revenge by killing women and children in the villages.”

[…]

[Mokhoyan resident Naek] Mohammad said a U.S. soldier, speaking through a translator, then said: “I know you are all involved and you support the insurgents. So now, you will pay for it — you and your children will pay for this.'”

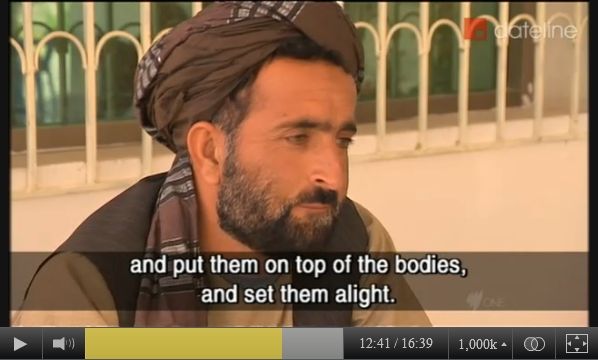

Similar information was conveyed in person (about two weeks after March 11th) to Australian-TV SBS Dateline reporter Yalda Hakim by the Afghan National Army General appointed as chief investigator of the Panjwai massacre by Afghan President Hamid Karzai:

GENERAL [Sher Mohammad] KARIMI: “Three days, four days – that’s what they said – before this incident, one of the US vehicles was hit by [a] mine, in a village [“called Mokhoyan,” Karimi says at this point per the video footage] in that vicinity, that area. One of the American soldiers lost his leg. He was amputated. This guy happens to be a very close friend to this individual, Robert Bales – close friend to this guy. And he had called the people – he had gone to the village – and told the people that he will revenge his friend, he will shoot everybody and gain revenge. That’s another issue that the people claim.”

[I learned April 21 – thanks to a translation in this “Exclusive” post – that the Spanish news agency ABC.es reported similar information on March 13, quoting one of the same named sources cited a week later in the AP article (a man who had apparently spoken at a March 12 news conference held by eyewitnesses and other villagers while Afghan police and military – including two of President Karzai’s brothers – were on-scene investigating): «Un artefacto estalló al paso de un vehículo en la zona de Zangabad, del distrito de Panjwai hace tres días», explicó este lunes uno de los líderes tribales, Haji Muhammad Shah Khan, en declaraciones citadas por AIP. «Más tarde, los soldados de EE.UU. reunieron a varias personas en la zona y les acusaron de haber puesto el artefacto. Dijeron que se vengarían y atacarían a las mujeres y niños de la zona», añadió. (Haji Muhammad Hassan, who apparently witnessed the attacks, is also quoted in the 3/13 ABC.es report, as is “26-year-old” Mohammad Zahir – mentioned below – the man who survived by going into the animal corral of his home.)]

Then, after midnight on the night of March 10-11, two nights after the alleged March 8th roadside bombing of an ISAF/NATO/American military vehicle, three different Afghanistan National Army soldiers on guard duty at the Camp Belamby base – located just west of where the Mokhoyan roadside bomb detonated – witnessed a single American soldier coming and going from the base, on foot, evidently during three consecutive shifts of guard duty by the Afghans.

As reported by Robert Burns of the Associated Press on Friday, March 23rd:

Members of the Afghan delegation investigating the killings said one Afghan guard [named Naimatullah, according to Yalda Hakim’s reporting] working from midnight to 2 a.m. on March 11 saw a U.S. soldier return to the base around 1:30 a.m. Another Afghan soldier who replaced the first and worked until 4 a.m. said he saw a U.S. soldier leave the base at 2:30 a.m. [apparently heading south, toward Balandi/Najiban, according to Hakim’s report]. It is unknown whether the two Afghan guards saw the same U.S. soldier.

And, as reported by Yalda Hakim on March 27th after also speaking to a third Afghanistan National Army soldier on guard duty that night (all three of the Afghan Army guards were filmed by SBS-TV cameraman Ryan Sheridan for the important 3/27 Dateline report), who likewise saw and quickly reported to his superiors an (unidentified) U.S. soldier approaching the base that night (a time is not given, but presumably sometime between 4 a.m. and 6 a.m. unless this soldier was on the same 2-4 a.m. shift as the second soldier quoted):

SOLDIER (Translation): I notified the foreign forces that someone is coming. They told us not to shoot because it’s one of theirs. When we went out [according to the translation used for the subtitles of the filmed footage, this guard said he did not return “outside” after alerting the “foreign forces” inside the camp about the approaching soldier] the foreign forces searched him [the arriving soldier], took his clothes, and brought him into the camp in his underwear.

The earlier March 17th BBC account (which is otherwise mostly quite vague and imprecise) put it this way [Note: The BBC source(s) may be the reporting of Mamoon Durrani, who gave me a similar account, with some differences (plus the important additional detail that there are two Camp Belamby entrances/exits – one facing north, and one facing south), for my subsequent July 7th post (see the closing paragraphs of the text area, and Comment 5 there)]:

An Afghan guard at the Nato base told the BBC that Sgt Bales left the base twice. He returned at 00:30 local time (20:00 GMT) after the first trip out and was out between 02:00 and 04:00 for the second trip.

[…]

The Afghan guard at the base told a BBC reporter that when the soldier returned to the base after the first trip out, he greeted them in rudimentary Pashto. [The guard named Naimatullah who Yalda Hakim interviewed on camera about witnessing an unidentified soldier returning to the base the first time (at 1:30 a.m. local time, not 00:30 a.m., according to Hakim), said that the returning soldier said something to him on his way into the camp that Naimatullah didn’t understand because it was in the U.S. soldier’s “own language.”]

Despite these and related, less-detailed reports (which omit basic facts like whether there’s more than one entrance/exit to Camp Belamby), it’s still unclear which settlement was attacked first that night (never mind whether we can even be sure of which village is one-half mile to the north, and which 1.5 miles to the south of Camp Belamby, or of what the real name(s) of those villages are…).

But Yalda Hakim’s 3/27 SBS report, apparently drawn from the eyewitness accounts (given to her in person the week before) of three Afghanistan National Army soldiers who saw, in turn, an American soldier arriving, an American soldier departing an hour later, and then an American soldier arriving again 1.5-3.5 hours after that, would seem to lend credence to Alkozai, about half a mile to the north of Camp Belamby, being the first targeted that night (which is how Hakim narrates the sequence of events in her footage).

An early March 12 Associated Press report [link broken; alternative link] quotes the Afghan Defense Ministry as saying that the first village targeted was Balandi/Najiban (1-2 miles to the south of Camp Belamby) – except that the 3 a.m. timing evidently reported by the villagers, and cited in the story, seems to bely that sequence of events (due to the since-revealed accounts and schedules of the Camp Belamby Afghan Army guards), and would instead closely align with Balandi/Najiban being the second village targeted that night, in line with Hakim’s 3/27 report:

The Afghan Defense Ministry said the gunman left the base in Panjwai district and walked about one mile (1,800 meters) to Balandi village. Villagers described how they cowered in fear around 3 a.m. [the timing should have been before 1:30 a.m., if Balandi was the first village targeted and Bales was the lone assailant] as gunshots rang out and the soldier roamed from house to house, firing on those inside. They said he entered three homes in all and set fire to some of the bodies [in the home of Mohammad Wazir] after he killed them.

Eleven of the 12 civilians killed in [or near] Balandi were from the same family [that of Mohammad Wazir, who was away overnight with his four-year-old son Habib Shah, visiting relatives some hours away in Spin Boldak]. The remaining victim was a neighbor [Mohammad Dawood, from outside the village, father of 6 – or 7, per the GlobalPost (whose reporter(s), like Yalda Hakim who cites 6 children, spoke to Dawood’s widow and brother) – young children].

From Balandi, the gunman walked roughly one mile [more like 1.5 miles, I think, passing Camp Belamby on the way] to the village of Alkozai [is AP‘s source for this still the Afghan Defense Ministry?], which was only about 500 meters from [north of] the American military base. There the gunman killed four people in

one house[the four acknowledged Alkozai deaths in fact occurred in three different houses; see Comment 13 below] and then moved to [Mohammad] Zahir’s [who’s possibly the farmer – or, per Comment 4 below, more likely the brother of – “Habibullah” in the GlobalPost.com storyvillage unknown,per Comment 13 below] house, where he shot his [Zahir’s] father in the leg.

Setting aside the question of which village settlement was attacked first, early accounts reported that 16 of the dead from both/some/all villages were quickly transported to the Camp Belamby base itself [or at least to its gates], no doubt facilitating the detailing of the 17 premeditated murder counts with which Bales was charged on March 23rd – in accordance with the UCMJ and its court-martial jury-of-peers system of due process, of course; somehow no MCAct-concocted, defense-handicapping, jury-trial-protection-spurning Military Commission seems to be necessary when American persons are alleged to have committed war crime atrocities on an active foreign battlefield.

This March 11th account is from the New York Times:

By TAIMOOR SHAH and GRAHAM BOWLEY

Published: March 11, 2012In Panjwai, a reporter for The New York Times [evidently Taimoor Shah] who inspected bodies that had been taken to the nearby American military base [Camp Belamby] counted 16 dead, including five children with single gunshot wounds to the head, and saw burns on some of the children’s legs and heads. “All the family members were killed, the dead put in a room, and blankets were put over the corpses and they were burned,” said Anar Gula, an elderly neighbor who rushed to the [Mohammad Wazir] house [in the southernmost village of Balandi/Najiban] after the soldier had left. “We put out the fire.”

The villagers also brought some of the burned blankets on motorbikes to display at the base, Camp Belambay, in Kandahar, and show that the bodies had been set alight. Soon, more than 300 people had gathered outside to protest.

At least five Afghans were wounded in the attacks, officials said, some of them seriously, indicating the death toll could rise. NATO said several casualties were being treated at a military hospital [on the Kandahar Airfield base].

Mohammad Wazir [who’s also called whose 60-year-old father – I learned late April 14 from this lengthy, valuable post by Gary Moore [a post that, by May 22, seems to have been removed from Moore’s site, without explanation], as noted in Comment 4 below – uncle (see Comment 19) apparently also survived (by being away from home), and, if so, is apparently is the man (and grandfather?) known as “Samad Khan” and “Haji Samad” and “Abdul Samad” in some early reporting], of the Panjwai district village of Balandi/Najiban:

Mohammad Wazir of Balandi/Najiban village in Panjwai district, Kandahar province, southern Afghanistan, speaking with Yalda Hakim of SBS-TV, Australia, at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital in Afghanistan in late March, 2012. All 11 of Mohammad Wazir's relatives at his home in Balandi were killed on the night of March 11, 2012 while he was away overnight (with his only remaining child). Here he's speaking of his 60-year-old mother.

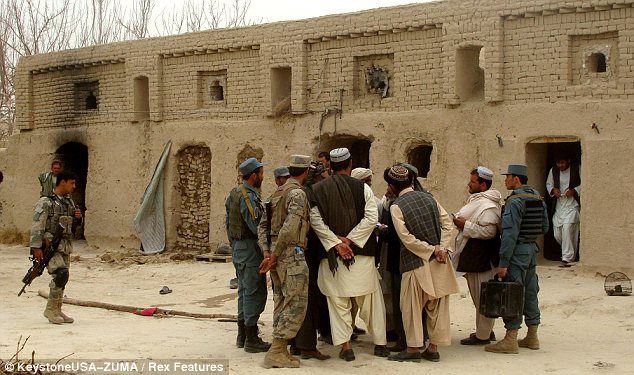

Judging by the evident smoke damage, this March 11 or March 12 photograph is probably the Mohammad Wazir home in Balandi/Najiban (the southernmost village), where 11 of Mr. Wazir’s family members – his mother, wife, 6 of his 7 children, his brother and the brother’s new bride, and a nephew – were shot and killed and then carried into the kitchen and set alight [all except Wazir’s mother, whose body was found lying near the door of the home’s main gate, as noted in Comment 17 below, and in my July 7th post]:

Appears to be a photograph of the Mohammad Wazir home in Balandi/Najiban, Panjwai district, where 11 family members were killed and 10 set afire on March 11, 2012. Photo Credit: KeystoneUSA-ZUMA / Rex Features

This March 11 photograph is of the interior of the room in the Mohammad Wazir home where the burning bodies were found by neighbors:

A March 11, 2012 photograph of the room in the Mohammad Wazir home in Balandi/Najiban where 10 of 11 murdered family members were carried by their attacker(s) to be burned on March 11, 2012. Photo Credit: Ahmad Nadeem/Reuters (The original caption was: Scene of the crime: Afghan men investigate at the site of a shooting incident in Kandahar province.)

[Most of] the seven or more wounded at Alkozai (apparently no one at Balandi/Najiban was wounded) were, at least initially, transported to and treated at the military hospital located on the major southern Afghanistan military base known as Kandahar Airfield, which gave the ISAF/NATO/Americans the ability to block access to the survivors when local Afghan journalists tried to speak to them (and, according to Yalda Hakim, also to block the local Afghan investigators to some extent). (“The wounded survivors, who saw everything of the massacre, are crucial to the story,” said one of the frustrated [Afghan] reporters. “But the Americans didn’t allow us to talk to them” – reported GlobalPost.com at the end of this March 23rd account, which identifies the hospital in question.) [At least one Afghan reporter, however, reportedly filmed the wounded at the hospital on March 12 – see my July 7th follow-up post.]

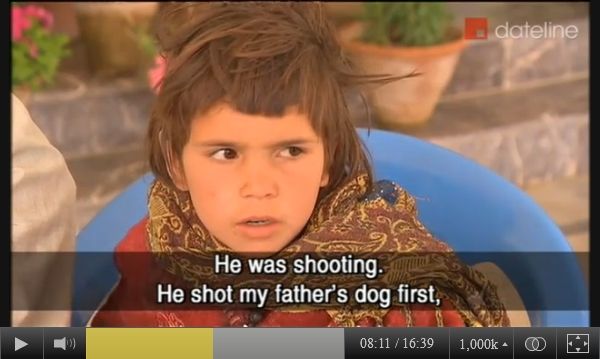

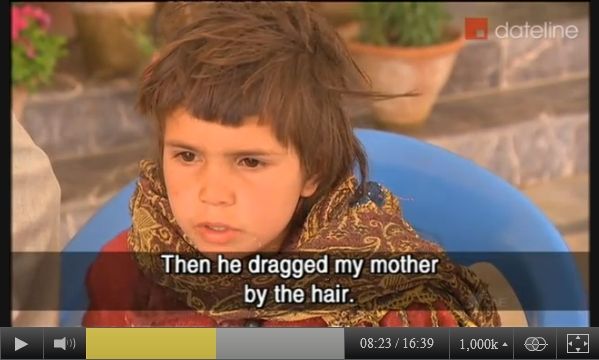

Yalda Hakim herself was initially prevented by the American military from speaking with survivors at the Kandahar Airfield base hospital, until her news director in Sydney contacted Afghan President Hamid Karzai, who told the Americans to grant Hakim access (Hakim had interviewed Karzai for SBS 4-5 weeks earlier). Karzai’s intervention allowed Hakim to film an interview at the hospital, a few days before March 27, with two wounded children – identified only as the boy Sediqullah, and 8-year-old girl Noorbinak (whose father was shot in the foot and chest/neck and killed), but who are, respectively, I’m deducing (based in part on Qais Azimy’s list of wounded, which includes “Mohamed Sediq, son of Mohamed Naim”), the wounded son of Mohammad Naim of Alkozai (who was also wounded), and one of the 3-4 children wounded in the household of Sayed Jan (Saaed Jaan) of Alkozai, where, it seems, the father of a Jan Agha (Jan Agha might be Noorbinak’s cousin?) was killed with three others (who were, apparently, Jan Agha’s mother, brother and sister). Hakim also spoke with several men at the hospital, including Mohammad Wazir of Balandi/Najiban, the late Mohammad Dawood’s brother Baran Akhon of Kandahar city (also called “Mullah Barraan” in some reports), and – I believe – [a cousin of] Sayed (or Saeed) Jan (or Jaan) of Alkozai (who, like Wazir, was away overnight when the killing of his family members occurred).

_________________________________________________________________

ALKOZAI

(About 1/2 mile north of Camp Belamby; where 4 were killed and 7 or more wounded) _________________________________________________________________

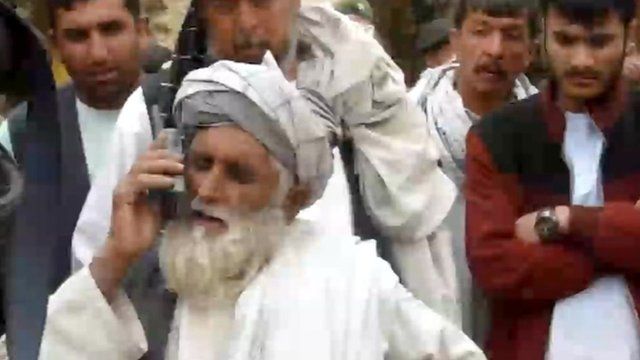

Based on the photo caption in this early, March 12 BBC account, I’d thought the following photo might be a photograph of Sayed (or Saeed) Jan (or Jaan), Age 50, who lost his wife, his brother, his cousin or brother-in-law (accounts vary) 35-year-old nephew, and 3-year-old granddaughter or 3-year-old nephew (accounts vary) niece in Alkozai [reportedly two Jan nephews (or one nephew and one niece, aka Noorbinak??) – 7-year-old Rafiullah and 8-year-old Shokriya – were wounded, as was a 6-year-old niece, Zardana, who was shot in the head]. But now – per Comment 4 below, and the April 22nd update posted toward the end of the Balandi/Najiban section below – information I’ve learned since the post was published makes it seem more likely almost certain that this is instead the 60-year-old father uncle (see Comment 19 below) of Mohammad Wazir, Abdul Samad of Balandi/Najiban (see the similar, but much clearer photograph of Abdul Samad – who lost eleven family members – in the next section):

March, 2012 photograph of a man who lost family members in the March 11, 2012 Panjwai district, Kandahar province, Afghanistan killings. Photo Credit: BBC (The original caption was: Man who lost several family members telephones appeal to President Karzai)

As can be seen, the reporting about victims that remains the most confused to date is that describing the four individuals killed and 3-4 wounded in (or from) the Sayed Jan household in Alkozai. There seem to be two or more different accounts about the same victims, told from the perspectives of different relatives, possibly including the 8-year-old girl Noorbinak who Yalda Hakim interviewed at the hospital, but who SBS-TV didn’t associate with any village or family – aside from showing a close-up of a blood stain inside an Alkozai home, just after Noorbinak describes how her father died (at the beginning of the 3/27 SBS Dateline “Anatomy of a Massacre” program):

MAN [Yalda Hakim’s translator] (Translation): You know where your father is?

CHILD [8-year-old Noorbinak] (Translation): He died.

REPORTER [Yalda Hakim]: How did he die?

CHILD (Translation): The Americans.

Screen-captured image of 8-year-old Noorbinak - family and village unidentified until July (her father's Nazar Mohammad of Alkozai) - speaking with SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim in late March, 2012, at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital where Noorbinak revealed the bullet wound in her leg. Noorbinak watched her father being shot and killed by American soldier(s) on March 11, 2012, as her father defended her mother in their home in Panjwai district, Kandahar province, Afghanistan.

As Noorbinak’s (presumed) relative or neighbor Sayed Jan (“Syed Jaan”) told the Wall Street Journal, for an important, carefully-reported story published March 22nd:

ASIA NEWS | Updated March 22, 2012, 11:05 p.m. ET

A version of this article appeared March 23, 2012, on page A7 in some U.S. editions of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Afghan Father Copes With Aftermath.

By CHARLES LEVINSON, YAROSLAV TROFIMOV and GHOUSUDDIN FROTAN

[…]

Mr. Jaan was away, on a trip to Kandahar city, when his wife, brother, brother-in-law and three-year-old nephew were killed. Two nephews, Rafiullah, 7, and Shokriya, 8 [possibly a niece, aka Noorbinak?? – who was shot in the leg and lost her father], were hit in the lower part of their bodies, but are expected to survive.

Mr. Jaan’s 6-year-old niece Zardana, shot in the head, was still lying unconscious in a Kandahar hospital earlier this week, and wasn’t expected to survive, he said.

U.S. defense officials on Thursday said the death toll in the massacre was 17, up from 16. They didn’t immediately explain the change.

Zardana had asked Mr. Jaan, 50, to bring back new clothes on a recent trip to the city, something he couldn’t afford. “Whenever I go to the hospital and see her, I remember that time and her request,” Mr. Jaan says. “I feel helpless and vulnerable, and just can’t hold back tears.”

[A cousin (named Fazal Mohammad) of] the same man (Sayed Jan) may be is [per subsequent reporting by Afghan journalist Mamoon Durrani] in the group screen-capture of survivors (sitting next to Noorbinak) being interviewed at the hospital by Yalda Hakim the same week the WSJ account was published:

Survivors of the Panjwai district shootings being interviewed by Australian SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim (in the green scarf) at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital in late March, 2012. Starting with Hakim, and going counterclockwise, they are the SBS-TV interpreter; 8-year-old Noorbinak (who was shot in the leg and whose father was killed in front of her); Fazal Mohammad (source: family through Mamoon Durrani), a cousin of Sayed Jan of Alkozai who lost 4 family members; Baran Akhon (the brother of the murdered Mohammad Dawood from near Najiban - Dawood's widow and 7 6 children are now living with Akhon); Agha Lala (40-50) of Najiban, who was killed in a car accident on June 30, 2012 (see end of 7/7 post); and, with his back to the camera, Mohammad Wazir (35) of Balandi/Najiban (11 members of Wazir's family were murdered on March 11, 2012).

Someone who I deduce [incorrectly? see Comment 16 below] to be a relative of Sayed Jan’s gave early accounts of the killings in the Sayed Jan home in Alkozai to Reuters and McClatchy (perhaps before Sayed Jan had returned from Kandahar city, where he’d spent the night?). That eyewitness is Jan Agha, Age 20, and according to some confused early reporting, Jan Agha watched his father be shot and killed at the window of their home in Alkozai that night, and then his mother and brother and sister were also killed. [A total of four dead have been reported in Alkozai (the northernmost village) as a whole.]

From one March 11th Reuters report:

By Ahmad Haroon

BELANDAI, Afghanistan | Sun Mar 11, 2012 2:22pm EDT

BELANDAI [though evidently reporting first about deaths that took place in the village of Alkozai], Afghanistan (Reuters) – Bursts of gunfire shook Jan Agha out of bed in his village in Afghanistan’s Kandahar province. His father peeped nervously through a window curtain at the lane outside.

Suddenly, more shots rang out. His father was hit in the throat and the face. He died instantly.

Afghan officials say Western forces shot dead 16 civilians including nine children in southern Kandahar province on Sunday in a rampage that witnesses said was carried out by American soldiers who were laughing and appeared drunk.

[…]

Agha, 20, said American soldiers who had opened fire in the early hours entered the family home and waited in silence for what seemed an eternity. He lay on the floor, pretending to be dead.

“The Americans stayed in our house for a while. I was very scared,” he told Reuters.

“My mother was shot in her eye and her face. She was unrecognizable. My brother was shot in the head and chest and my sister was killed, too.”

Agha’s account of multiple American soldiers shooting villagers could not be immediately verified.

From a second Reuters report co-bylined by the same reporter, that was published four hours after the first and doesn’t mention Jan Agha at all:

By Ahmad Nadem and Ahmad Haroon

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan | Sun Mar 11, 2012 6:19pm EDT

[…]

“I saw that all 11 of my relatives were killed, including my children and grandchildren,” said a weeping Haji Samad [evidently Mohammad Wazir’s

fatheruncle, of Balandi/Najiban], who said he had left his home a day earlier.The walls of the house were blood-splattered.

“They (Americans) poured chemicals over their dead bodies and burned them,” Samad [Mohammad Wazir’s

fatheruncle] told Reuters at the scene.Neighbors said they had awoken to crackling gunfire from American soldiers, who they described as laughing and drunk.

“They were all drunk and shooting all over the place,” said [Balandi] neighbor Agha Lala [no relation to Jan Agha of Alkozai, according to the first Reuters account], who visited one of the homes [the Wazir home in Balandi] where killings took place.

“Their (the victims’) bodies were riddled with bullets.”

Jan Agha is also quoted (this time, oddly, without any reference to his own losses) in a confused McClatchy report from March 11th, updated March 12th, which evidently understood the Jan Agha-described killings in Alkozai to the north to be killings that occurred to the south in “Gerambai”/Balandi/Najiban – or else mistakenly thought (perhaps based on the erroneous BBC map) that “Gerambai”/Belandi-Pul/Balandi/Najiban was the northern village, not the southern village, as other media reports clearly describe it to be…:

By Jon Stephenson and Ali Safi | McClatchy Newspapers

last updated: March 12, 2012 11:13:05 AM

[…]

Jan Agha, who lives near the site of the incident, told McClatchy the U.S. soldier attacked two houses in the village of Gerambai [meaning Najiban/Balandi to the south, apparently] as well as two houses in Belandi-Pul [meaning Alkozai, evidently?], four kilometers away, including [at Alkozai/”Belandi-Pul”] the home of his brother-in-law, Mohammad Naim. He confirmed the government account of dead and injured.

“In Belandi [that is, necessarily, to the north in Alkozai], four civilians were martyred (killed), and five wounded,” said Agha. He said his brother-in-law, Naim, and Naim’s son and daughter were among the wounded in Belandi [that is, in Alkozai to the north].

“In the house next to his [it’s unclear who “his” is a reference to here, but presumably Jan Agha means next to Mohammad Naim’s house], Sayed Jan’s house, four people were killed and two [or three] were wounded,” he added [without mentioning to McClatchy that those four killed were his close relatives too??].

Twelve people were killed [to the south] in Gerambai [Najiban/Balandi], Agha said – 11 in a house belonging to a farmer named Haji Wazir, who was away at the time.

“Their rooms were set on fire after they were killed,” Agha said. “I saw the house that was burnt,” he added. “This wasn’t the work of just one person.”

[Note, too, that this AP article cites “community elder Jan Agha” as a source for the amount of money “President Obama” paid the families of the victims. Perhaps (as later occurred to me, leading me to add this sentence in late May) Reuters and McClatchy are referring to two different Jan Aghas, and only “community elder” Jan Agha is a brother-in-law of Mohammad Naim? (See Comment 13 below.)]

In fact, according to a map later drawn for GlobalPost.com by one of the Alkozai eyewitnesses (Habibullah), it appears that at least three neighboring homes in that northernmost village were entered that night – the Sayed Jan (or Saeed Jaan) home, the home of Mohammad Naim, and which is apparently also that of 28-year-old farmer Habibullah (see Comment 13), and the home of Nazar Mohammad (as revealed by new reporting on May 16). [Habibullah might be probably isn’t (see Comment 13) the brother – see Comment 4 below – of 26-year-old “Mohammad Zahir” (Zahir’s village isn’t named) referenced in this March 12th AP report – whose father was wounded.] From the March 23rd GlobalPost report [print page “no longer available” 10/8; replacement link] quoting Alkozai resident Habibullah:

By Bette Dam March 23, 2012 06:29 Updated March 29, 2012 08:10

[…]

Habibullah, a 28-year-old farmer who saw parts of the massacre unfold, was one of those who met Karzai [on Friday, March 16th]. He told GlobalPost he saw several soldiers in his compound when his father was shot [and wounded]. But he also admits he can’t remember everything that happened.

“My mind is too confused,” he said.

Habibullah tried his best to describe the shooting for GlobalPost. He drew a map of the three houses in his village, Alkozai, where four people were killed. His house was in the middle. He said his wife woke him up early in the morning — he can’t recall the exact time — shouting that American soldiers were at the house next door. Habibullah told her not to worry.

“This is a night raid,” he remembered telling her.

[…]

But a few moments later residents from neighboring houses began fleeing to Habibullah’s, telling everyone to hide. The attacker — or attackers — soon followed, he said.

“I didn’t hear a lot of shooting and I didn’t hear helicopters,” Habibullah recalled. But he did see “two or three Americans” enter his compound, “using lights and firing at my father, who was wounded.”

“Next” to the Sayed Jan home (or close by, on the other side of the Habibullah home) in Alkozai is the home of Mohammad Naim (and, evidently, his son Habibullah), who is the brother-in-law of Jan Agha (Jan Agha presumably was living in the Sayed Jan home, though there’s no real evidence of that). Three occupants were wounded in the Naim home – Mohammad himself, his son, and his daughter – as were neighbors who fled there, one of whom was killed: see Comment 13. Assuming We now know that the wounded boy filmed at the hospital is Mohammad Naim’s son; “Sediqullah” was shot near the head:

Young Panjwai boy Sediqullah - son of Mohammad Naim of Alkozai - pointing to the near-miss bullet wound in the ear he received in the Panjwai Massacre on March 11, 2012, during an interview - apparently at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital - with SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim in late March, 2012

More of a mystery, unfortunately, is which family the young girl Noorbinak [who’s apparently also known as “Robina,” per Article 32 testimony in November, 2012] belongs to. Because her father was killed, she evidently has to belong to either the Sayed Jan household family in Alkozai, or to the Mohammad Dawood home in near Balandi/Najiban. But there’s no indication from the hospital interview footage (where Baran Akhon – Dawood’s brother, who would thus be her uncle – is sitting across from Noorbinak) that she belongs to that Balandi/Najiban family of six children [by most accounts, and (by my count) all accounted for in Kandahar city with their mother in the SBS Dateline footage aired 3/27] or, by one account, 7 children (I believe 7 children are visible at times in the same DatelineSBS footage of the Dawoods). Notice, in the third screen capture of the SBS footage below, how Noorbinak places her hand near her neck to indicate where her father was fatally shot [after he was first shot in the foot; whereas Mohammad Dawood, based on the accounts of his widow and brother cited further below – and on an April 11 account by SBS-TV’s Yalda Hakim (see Comment 2) – was evidently fatally shot in the head]:

Yalda Hakim and her cameraman Ryan Sheridan visited at least one of the homes in Alkozai (without the survivors present) for her report – on March 23rd, according to this tweet – but apparently did not go south to Balandi/Najiban. At about the same time that Hakim was making her way through allegedly newly-mined roads and fields to visit Alkozai (while apparently being told by her Afghan Army/Police guides that all Alkozai residents had fled the settlement in fear for their lives), Mirwais Khan and Heidi Vogt of the Associated Press published a very informative, detailed follow-up account about some of the Alkozai survivors, on Saturday, March 24th:

By MIRWAIS KHAN and HEIDI VOGT

HARMARA, Afghanistan —

[…]

Another man whose wife, cousin, brother and 3-year-old granddaughter were killed in the neighboring village of Alkozai said people there are too scared to sleep alone, so they cram as many people into one house as possible each night. Saeed Jan also complained that U.S. troops continue to patrol the area.

“There is still blood in our houses. It hasn’t been removed. And they are moving through our streets again. It’s like they are pushing us, just showing that they can,” Jan said.

He also says monetary payouts will not suffice.

“Even millions of dollars would not be enough for my brother. First they should give us justice and punish all the people who did this,” [Baran] Akhon said [speaking of his brother Mohammad Dawood, father of 6-

7young children, who was killedinnear Balandi/Najiban].

There’s another eyewitness account – which, if his age is inaccurately reported, might be another son recounting the killing of the father of (20-year-old) Jan Agha (or of 8-year-old Noorbinak?) in Alkozai, or (though much less likely) perhaps the killing of Mohammad Dawood that I can’t place for certain in either village, or in any of the three homes evidently entered in Alkozai. That account is from this March 11th New York Times report:in near Balandi/Najiban –

By TAIMOOR SHAH and GRAHAM BOWLEY

Published: March 11, 2012

[…]

One of the survivors from the attacks, Abdul Hadi, 40, said he was at home when a soldier broke down the door.

“My father went out to find out what was happening, and he was killed,” he said. “I was trying to go out and find out about the shooting, but someone told me not to move, and I was covered by the women in my family in my room, so that is why I survived.”

Mr. Hadi said there was more than one soldier involved in the attacks, and at least five other villagers described seeing a number of soldiers, and also a helicopter and flares at the scene. But that claim was unconfirmed — other [unnamed…] Afghan residents described seeing only one gunman — and it was unclear whether extra troops had been sent out to the village after the attack to catch the gunman [they were preparing to search but had not yet left the base when Bales returned and was taken into custody, as subsequent information makes clear – pow wow].

[See Comments 12 and 13 below for valuable new details about the shootings and victims in Alkozai, which were reported by McClatchy in a May 16th article and accompanying graphic (link broken in their 9/24 website redesign; alternative link). Those details and more are expanded upon in my second, July 7th follow-up Panjwai post.]

_________________________________________________________________

BALANDI/Najiban [& DAWOOD Home (see Comment 19 below)]

(About 1.5 miles to the south of Camp Belamby; where 12 were killed and none wounded) _________________________________________________________________

There’s more precise detail from eyewitnesses to the killings and/or their aftermath in the southernmost Balandi/Najiban village [and the nearby Dawood home (see July 7th post)] – due in part to the dramatic nature of the Wazir family tragedy there, and possibly also because it may not have been clear at first that a second (and third?) village to the north was also targeted, so that reporting and photography early on focused mostly on the Balandi/Najiban survivors.

There are reports of direct attacks on two homes in [or near] Balandi/Najiban: The home of Mohammad Dawood [which I learned in late June is located about one-half kilometer east/northeast of Balandi/Najiban] and the home of Dawood’s neighbors Mohammad Wazir and Abdul Samad (Wazir’s father uncle) [which is located in Balandi/Najiban village proper].

A Balandi/Najiban neighbor of the two Wazir/Samad home attacked there, Agha Lala, was an eyewitness to the attackers outside those that dwelling – and, because Lala himself was not being directly attacked at the time, and evidently watched the attackers for some time (before being shot at himself and then hiding), Agha Lala is probably a particularly valuable and credible eyewitness as to the (multiple) number of attackers (or at least attack conspirators/helpers) in Balandi/Najiban that night. So far, however, I’ve seen only this one brief Reuters report, from March 11th, quoting Agha Lala by name about what he saw [similar comments by Agha Lala are also quoted in another (later) March 11 Reuters report]:

By Ahmad Haroon

BELANDAI, Afghanistan | Sun Mar 11, 2012 2:22pm EDT

[…]Another witness, Agha Lala, who is in his 40s, said he was awoken by gunfire at about 2 a.m. [that timing, if accurate, doesn’t appear to match – for either village – if Bales was a lone assailant]

“I watched them from a wall for a while. Then they opened fire on me. The bullets hit the wall. They were laughing. They did not seem normal. It was like they were drunk,” he said.

After rushing to his home and hiding all night, Lala, who is no relation to Jan Agha, went to check on the neighbors [at the Wazir and Dawood homes in/near Balandi/Najiban].

“It was a slaughter. The bullet-riddled bodies were all over the room and it seemed they were burned with curtains and blankets that were torched,” he said.

“Is this what the Americans call an assistance force? They are beasts and have no humanity. The Taliban are much better than them.”

Blood was splattered in one house in the village and there were bullet holes in the walls.

On March 23rd, Reuters also made available here a 2-minute clip (that I haven’t been able to view), with a brief transcript that indicates that it contains footage of a sentence or two spoken, in Pashto, by an “Agha Lala” – who may be the same man, and/or the “Kandahar provincial council member Agha Lalai” quoted in this article, or someone else with the same name – about bringing the Panjwai killer(s) to justice [(SOUNDBITE) (Pashto) KANDAHAR RESIDENT, AGHA LALA, SAYING: “We demand from the court in the United States to give the death penalty to the U.S soldier who massacred the civilians, because he deserves hanging, because he committed the biggest crime. We want a punishment based on Islamic sharia law.”].

[See the last photograph in my July 7 follow-up post, and Comment 4 there, for more about Agha Lala.]

[April 27 Update: As referenced near the beginning of the post – and thanks to a tweeted link to a Truthout reprinting of this April 23rd post by Ralph Lopez, which updated a longer, skeptical 4/23 overview of the conflicting Panjwai reporting, that provided a link to a March 21 post at Salon.com by Jefferson Morley – I discovered an important March 19 CNN International video that was narrated by Sara Sidner for NEWS STREAM, which apparently includes another key eyewitness account from an adult male in Balandi/Najiban at the Dawood Home [see July 7 post], of whom I had not previously been aware (and who represents [pre-July 7 post] only the third second named adult eyewitness in Balandi/Najiban at the Dawood Home). That eyewitness – Ali Ahmad (see screen capture below) – is almost certainly describing Mohammad Dawood as his uncle, and CNN translated and transcribed Ali Ahmad’s account of the Dawood home attack (and the “next door” to the attack on the Mohammad Wazir/Abdul Samad home [which is actually about one-half kilometer away from the Dawood home]) as a “witness” account, as follows.]

SIDNER (voice-over): Graves in

Majabianvaj (ph)Najiban, a place now haunted by the memory of a massacre.Ali Ahmed (ph)Ali Ahmad describes what he saw. “It was around 3:00 at night that they entered the room. They took my uncle out of the room and shot him after asking him, ‘Where is the Taliban?’ My uncle replied that he didn’t know.”Ahmed (ph)Ahmad said the worst happened next door. “Finally, they came to this room [in the Mohammad Wazir/Abdul Samad home] and martyred all the children in the room. There was even a 2-month-old [2-year-old?] baby,” he said.

Once the shooting stopped, the villagers said some of the dead were piled in a room and set on fire. At daybreak, in the back of trucks, evidence emerged of the burning of bodies and killing of babies.

[…]

“They went through a field of wheat and there was more than one set of footprints. The villagers have seen them and signs of knee prints as well.”

And here’s how Sidner and/or her editors put it in the CNN article describing the same video footage:

Ali Ahmad, one of the villagers, holds a blood-stained pillow in his home, then goes to his neighbor’s home and shows blood splatter on a wall as he describes what he remembers.

“It was around 3 at night that they entered the room. They took my uncle out of the room and shot him after asking him, ‘Where is the Taliban?’

“My uncle replied that he didn’t know,” Ahmad said.

Ahmad used “they” but did not say more than one soldier was in his home. [Adds CNN, inexplicably – confusing rather than clarifying their translation of Ahmad’s words, which seem to belie this statement. – pow wow]

[…]

Most of the villagers say they do not believe the U.S. version of events, but accounts from eyewitnesses conflict.

One of the young [Dawood?] boys who were there recounted it this way:

“He said, “Hello, hello Taliban, Taliban. We told him there is no Taliban here, but he broke the cupboards.” He added, “He was an American.”

Another boy chimes in: “It was just one person.”

And although some adults in the village said they have evidence more than one soldier was involved, none has said that more than one soldier was firing a weapon.

“They went through the field of wheat and there were the footprints of no less than 15 people. There were signs of knee prints as well.” Ahmad said.

Ali Ahmad (center), apparently an eyewitness to the murder of Mohammad Dawood in a home near Balandi/Najiban on March 11, 2012. Ahmad's a nephew of Mohammad Dawood, and, according to the CNN translation, Ahmad said that soldiers took Dawood out of the room that they had entered, and then shot Dawood, at about 3 a.m. on 3/11/2012 after asking Dawood: Where is the Taliban? From undated footage aired by CNN International on March 19, 2012. (I subsequently learned - see July 7 post - that Ali Ahmad is named Toor Jan, and that Toor Jan is in fact a nephew of Mohammad Dawood (and Baran Akhon). The man in white on the right in this screen capture is another brother of Mohammad Dawood named Abdul Woddod, per Baran Akhon.)

[The March 18/March 19 CNN International video includes footage of what seems to be the backyard of either the Wazir/Samad home in Balandi/Najiban or the Mohammad Dawood home. The villagers took the cameraman back there to point out something by the wall (apparently on the ground near an old oil drum and smaller red fuel container), but just as the camera appears to be focusing in on the area in question, CNN cuts away from that footage to something else.]

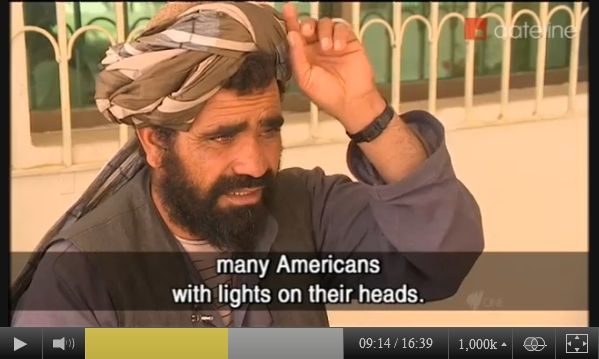

Here’s a screen capture from the March 27 SBS-TV Dateline report, showing several of Mohammad Dawood’s 6 (or 7) children (from near Balandi/Najiban) – at least six young children are visible around their mother, Mohammad Dawood’s widow Massouma, in the Dateline footage filmed [by Yalda Hakim at night] shortly before 3/27 – after their relocation to the simple (unelectrified) home in Kandahar city where Dawood’s brother Baran Akhon has taken in Dawood’s widow and children, including the 6-month-old in his mother’s arms who’s referenced in the screen capture of Baran Akhon further below:

Three of the six (or seven) children of Mohammad Dawood from near Balandi/Najiban village, Panjwai district, Kandahar province, Afghanistan. Mohammad Dawood was attacked and murdered at his home on March 11, 2012 (by a group of American soldiers, according to his widow Massouma and nephew Ali Ahmad/Toor Jan). Dawood's brother Baran Akhon brought his brother's family to live with him in his modest home (unwired for electricity) in Kandahar city, Afghanistan, where Australian SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim personally filmed this scene with a hand-held camera (because her male cameraman Ryan Sheridan was not allowed into the home) in late March, 2012

Baran Akhon ("Mullah Barraan"), the brother of the late Mohammad Dawood - who was murdered near Balandi/Najiban on March 11, 2012 in front of his wife and 6 children. Baran Akhon is describing to SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital, late in March, 2012, what Dawood's widow and children have told him about what they witnessed the night that Mohammad Dawood was killed, after the six-month-old became frightened by the screaming

Mohammad Dawood’s widow and her young children [and per the 4/27 update, Dawood’s adult nephew Ali Ahmad/Toor Jan, as well] are some of the few, key eyewitnesses to the attack in Balandi/Najiban at the Dawood Home that night. given that [In the nearby village of Balandi/Najiban,] no one (save possibly one adult sister – see Comment 4 below) was spared in the neighboring home of Mohammad Wazir, where all 11 were reported killed. As Yalda Hakim – who was born in Afghanistan and speaks the languages – explained in a radio interview after her 3/27 Dateline report, it is rare for Afghan women and children to be put forward in public to the extent that she and her cameraman were granted access to Dawood’s widow and children [and to the two children (of the Naim and Jan families?) at the hospital, whose mothers – if not wounded or killed – are never on camera]. No doubt for similar reasons, Dawood’s brother Baran Akhon was reluctant at first to let a GlobalPost.com reporter interview Dawood’s widow directly – although you’d never know that was the reason from GlobalPost’s insensitive, condescending article about their interviews with Baran Akhon and Dawood’s widow (see below). So we owe a debt of gratitude to Yalda Hakim and colleagues, and to the survivors themselves, for the existence of important eyewitness accounts from Mohammad Dawood’s widow, and from her children, including indirectly through their uncle, Dawood’s brother Baran Akhon.

Baran Akhon ("Mullah Barraan"), the brother of the late Mohammad Dawood - who was murdered near Balandi/Najiban village, Panjwai district, on March 11, 2012 in front of his wife and 6 -7 children. Baran Akhon is describing to SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital, late in March, 2012, what Dawood's widow and children have told him about the group of American troops they saw at their home the night that Mohammad Dawood was killed

MULLAH BARRAAN [aka Baran Ahkon, brother of Mohammad Dawood] (Transcript/Translation): The Americans left the room, my brother’s children say they saw in the yard many Americans with lights on their heads and they had lights at the ends of their guns as well. They don’t know whether there were 15 or 20, or however many there were.

[Note that Barraan/Akhon is apparently referencing accounts from the same two Dawood boys shown in the CNN screen capture near the beginning of the post (who both spoke of seeing a single soldier), but he’s referencing what the children saw “in the yard” (where Mohammad Dawood was shot and killed) as opposed to in the home.]

Baran Akhon ("Mullah Barraan"), the brother of the late Mohammad Dawood - who was murdered near Najiban village, Panjwai district, on March 11, 2012 in front of his wife and 6 -7 children. Baran Akhon is describing to SBS-TV reporter Yalda Hakim at the Kandahar Airfield ISAF military hospital, late in March, 2012, what Dawood's widow and children have told him about the group of American troops they saw at their home the night that Mohammad Dawood was killed

[Note this photograph of one version of Pentagon contractor SureFire’s weaponlights (and assorted helmet lights and headlamps) that Ralph Lopez posted in his two recent articles examining Panjwai reporting (Lopez called them “standard night-raid equipment for US forces” and “standard weapons/helmet lights for night raids”). Does the U.S./ISAF soldier shown in the last photograph on this page have such a light attached to his weapon and/or to his helmet?]

Here’s what Dawood’s widow told Yalda Hakim, shortly before March 27, during the interview screen-captured above:

I travelled back to the city of Kandahar, where I want to speak to one more survivor – Aminea – not her real name – now lives here [in Dawood’s brother’s home] with her six children in a mud hut with no electricity.

AMINEA [Dawood’s widow] (Translation): As I was dragging him [Mohammad Dawood] to the house, his brain fell into my hand and I put it into a clean handkerchief. There was so much blood – as if three sheep had been slaughtered.

Of all the stories I heard on this trip, hers was the most wrenching account of how the killings have changed this country. And how Afghan people now fear the soldiers who had promised to help them and protect them.

AMINEA [Dawood’s widow] (Translation): I had no feeling other than… if I could lay my hands on them, if I could lay my hands on those infidels, I would rip them apart with my bare hands. [A fierce defensive spirit that may have been responsible for the fact that she and her 6 young children somehow escaped unharmed, aside from the loss of their husband and father. – pow wow]

On March 22nd, Mohammad Dawood’s brother described to the Wall Street Journal part of Dawood’s widow’s eyewitness account, and his own experiences after arriving at the killing scene (presumably from his home in Kandahar city):

“The only people who have remained are those who couldn’t afford the expense of moving their families to the city,” says Mullah Baran [Akhon], a 38-year-old whose brother, Mohammad Dawood, was the first

[Balandi/Najiban?]victim of the March 11 rampage, according to witnesses to the shooting, and other villagers. “The Americans said they came here to bring peace and security, but the opposite happened. Now, this village is a nest of ghosts.”Mr. Baran, who says he had to scrape his brother’s brain and pieces of skull from the floor of their home, lost only one relative. His brother’s wife started screaming at the intruder, he says, and the gunman spared her and her six children.

On March 23rd, the referenced GlobalPost.com article recounted their interview with Mohammad Dawood’s widow this way:

[Afghan President Hamid] Karzai also spoke to Mullah Baran [Akhon]. Baran’s brother [Mohammad Dawood] was killed in the shooting spree, but he [Baran Akhon] didn’t see the shooting happen. Baran said he told Karzai what his sister-in-law [Dawood’s widow], who was at the scene, had told him.

When GlobalPost asked Baran to speak directly with his sister-in-law [Dawood’s widow], he initially refused.

“You don’t need to talk her,” Baran said. “I did, and I can tell you the story.”

Eventually Baran relented, allowing GlobalPost to interview her [Dawood’s widow] by phone.

Massouma [widow of Mohammad Dawood], who lives in the neighboring village of Najiban, where 12 people were killed, said she heard helicopters fly overhead as a uniformed soldier entered her home. She said he flashed a “big, white light,” and yelled, “Taliban! Taliban! Taliban!”

Massouma said the soldier shouted “walkie-talkie, walkie-talkie.” The rules of engagement in hostile areas in Afghanistan permit US soldiers to shoot Afghans holding walkie-talkies because they could be Taliban spotters.

“He had a radio antenna on his shoulder. He had a walkie-talkie himself, and he was speaking into it,” she said.

After the soldier with the walkie-talkie killed her husband, she said he lingered in the doorway of her home.

“While he stood there, I secretly looked through the curtains and saw at least 20 Americans, with heavy weapons, searching all the rooms in our compound, as well as my bathroom,” she said.

After they completed their search, the men left, Massouma said. She said that all seven of her children saw the attackers, but she refused to let GlobalPost speak with them.

An Afghan journalist who went to Massouma’s home in the days after the shooting and spoke with one of her sons, aged seven, said the boy told him he looked through the curtains and saw a number of soldiers — although he couldn’t say how many.

The valuable follow-up article from the Associated Press on March 24 includes this further detail:

Baran Akhon, whose brother Mohammad Dawood was also killed in Balandi, said he’s not sure how he is going to support his brother’s family. He has brought all of them to live with him in Kandahar city, but he barely makes enough selling cigarettes and other small items from his pushcart to support his own family.

Turning to the slaughter in Mohammad Wazir’s family home [located about one-half kilometer west/southwest of the Dawood home – see my July 7th post] close to the Dawood home in Balandi/Najiban, we have multiple consistent, if basic, accounts of what Wazir witnessed when he returned from Spin Boldak with his four-year-old son Habib Shah early on the morning of March 11th.

[April 22 Update: Thanks to a March 12 New York Times account by Taimoor Shah and Graham Bowley that I’d not previously seen, and to the caption on the following photograph included in their article (see the similar, but low-resolution BBC photo posted above), I was able to confirm today that the man in the photo below, speaking by “satellite phone” (on Sunday, March 11, 2012) to President Karzai, is Abdul Samad, the “60-year-old” father uncle (see Comment 19 below) of 35-year-old Mohammad Wazir of Balandi/Najiban.]

According to the New York Times, this is a March 11, 2012 photograph of Abdul Samad - the 60-year-old father uncle of 35-year-old Mohammad Wazir - of Balandi/Najiban, Panjwai, who had 11 family members (including his wife and 7 grandchildren) murdered on March 11, 2012, while he was away overnight. Photo Credit: Anzala Khilji, New York Times. (The original caption was: Abdul Samad, an Afghan who had 11 relatives killed in a massacre, expressed his outrage to President Hamid Karzai.)

From the New York Times article accompanying that photograph – an article that muddled its early accounts of family relationships and residence locations, but included this valuable information:

By TAIMOOR SHAH and GRAHAM BOWLEY

Published: March 12, 2012PANJWAI, Afghanistan — Displaced by the war, Abdul Samad finally moved his large family back home to this volatile district of southern Afghanistan last year. He feared the Taliban, but his new house was nestled near an American military base, where he considered himself safe.

But when Mr. Samad, 60, walked into his mud-walled dwelling here on Sunday morning and found 11 of his relatives sprawled in all directions, shot in the head, stabbed and burned, he learned the culprit was not a Taliban insurgent.

[…]

“Our government told us to come back to the village, and then they let the Americans kill us,” Mr. Samad said outside the military base, known as Camp Belambay, with outraged villagers who came to support him. […]

After years of war, Mr. Samad, a poor farmer, had been reluctant to return to his home in Panjwai, which was known in good times for its grapes and mulberries.

But unlike other displaced villagers who stayed in the city of Kandahar, about 15 miles away, and other places around the troubled province, Mr. Samad listened to the urgings of the provincial governor and the Afghan Army. They had encouraged residents to return and reassured them that American forces would protect them.

Back in his village, a collection of a few houses known as Najibian, Mr. Samad and his family moved into a neighbor’s house because his own had been destroyed by NATO bombardments in the years of fierce battles.

[…] The districts [near Kandahar city] became ground zero for the surge of force ordered at the end of 2009 by the Obama administration.

There had been little to no coalition presence in the area in the decade since the war began, and American soldiers fought hard over the past two years to clear Taliban fighters from the mud villages like Mr. Samad’s that dot the area.

[…]

“Taliban are attacking the bases, planting mines, and the bases are firing mortars and shooting indiscriminately toward the villages when they come under attack,” said Malak Muhammad Mama, 50, a villager who now lives in Kandahar. He said that a month ago, a mortar fired from the base killed a woman, and that last week a roadside bomb hit an American armored vehicle.

[…]

As for Mr. Samad, he said he was in too much despair to even think about how he would carry on with his life. But he said the lesson of the deadly shootings was clear: the Americans should leave. Mr. Karzai called Mr. Samad on Sunday [March 11] after the killings, and Mr. Samad, barefoot as he spoke plaintively into a satellite phone with district officials gathered around, told the president: “Either finish us or get rid of the Americans.”