Since posting my last on-line diary preceding this one, in October, 2011 (as reposted just below this diary on the Home Page), some crucial developments and milestones in the American courts and Congress have transpired, that are deserving of all the attention we can give them. Thankfully, many others were on the case, speaking and writing with conviction and passion to anyone who would listen – which, predictably, didn’t include most of our incumbent elected representatives. As I catch up on some of the on-line contributions I missed over the last 3-4 months, and take the helm of the new DebatingChambers site, I plan to update this launch-post (or a subsequent post) with links to some of that important commentary and analysis. Meanwhile, in this post I’ll try to highlight the path down which recent inhumane actions of public officeholders in our Congress and federal judiciary are taking us, with help from the far-reaching perspective provided by an important new piece of habeas corpus scholarship.

Last month, of course, saw the tolling [the link is to a powerful and insightful piece in the National Law Journal by U.S. Army Major Todd Pierce, of the DOD’s OMC/Office of Chief Defense Counsel] of the disgraceful tenth anniversary, on January 11, 2012, of the opening of an American military prison in Cuba, that was deliberately designed (obviously, very successfully) to evade both the restrictions of domestic American law and any restrictions nominally imposed by the “law of nations” and its subsidiary “law of war,” on the treatment and disposition of its prisoners. While the month before that, there was, and is, the Buck McKeon/Carl Levin National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2012, now Public Law 112-81, after President Obama signed it into law on December 31, 2011 [in text or pdf format, when the law is available at the GPOffice, which it [now, on 3/30/12] is not at this time, in either format; meanwhile see this link for the final bill text].

In particular, there’s the section of that mammoth piece of NDAA legislation entitled “Detainee Matters” – in Subtitle D of Title X of Division A of the version that first passed the Senate 93-7 on 12/1/2011 – which was adopted, in final Conference Report form, 283-186 in the House on December 14th, and 86-13 in the Senate on December 15th. [Though the House/Senate conference report had only been issued on December 12th, five days after the House conferees had been appointed on 12/7 (Senate conferees were appointed on 12/1).]

Here’s how the Congressional Research Service summarized the version of the language that 93 incumbent Senators voted to adopt on 12/1, in Carl Levin’s Senate version of the bill, S. 1867 (which came out of the Senate Armed Services Committee that Levin chairs, on 11/15/11, without a written report – after being marked-up by the Committee in closed session last June); see also H.R. 1540, and earlier CRS summaries of the legislation [my emphasis and bracketed/indented comments]:

Subtitle D: Detainee Matters –

(Sec. 1031) Affirms that the authority of the President to use all necessary and appropriate force pursuant to the [2001 (Public Law 107-40)] Authorization for Use of Military Force includes the authority for U.S. Armed Forces to detain [somewhere] covered persons pending disposition under the law of war. Defines a “covered person” as a person who: (1) planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks on the United States of September 11, 2001, or harbored those responsible for such attacks; or (2) was part of or substantially supported al Qaeda, the Taliban, or [unspecified] associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its [unspecified] coalition partners. Requires the Secretary to regularly brief Congress on the application of such authority.

- Back on November 1, 2011, Steve Vladeck described this section very well, writing: “In one fell swoop, the NDAA thereby severs the requirement that detention be tied to a group’s responsibility for the September 11 attacks; overrides international law by authorizing detention of individuals who may have never committed a belligerent act; and effectively converts our conflict against those responsible for September 11 into a worldwide military operation against a breathtaking array of terrorist groups engaged in hostilities against virtually any of our allies.” (Just as the Executive Branch has been advocating in Guantanamo habeas cases for years, with the full-throated support of a radical D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals – the only lower appellate court to which they must answer in these cases; no “circuit splits” possible. This profoundly-consequential decision was made after exactly how many open, public – or even “closed” – hearings were convened, about the new, unbounded 2011 NDAA-AUMF, by the Senate Armed Services Committee, or by any other Senate committee of jurisdiction??) – pow wow

(Sec. 1032) Requires U.S. Armed Forces to hold in custody [somewhere…] pending disposition a person who was [according to whom…?? That‘s where the whole problem began and begins, with Army Regulation 190-8** having been shredded by 2002 presidential decree (see Comment 9)… – pow wow] a member or part of al Qaeda or an [unspecified] associated force and participated in planning or carrying out an attack or attempted attack against the United States or its [unspecified] coalition partners. Authorizes the Secretary to waive such requirement in the national security interest. Makes such requirement inapplicable to U.S. citizens or U.S. lawful resident aliens. Outlines implementation procedures.

- **Army Regulation 190-8, in part: “b. A competent tribunal shall determine the status of any person not appearing to be entitled to prisoner of war status who has committed a belligerent act or has engaged in hostile activities in aid of enemy armed forces, and who asserts that he or she is entitled to treatment as a prisoner of war, or concerning whom any doubt of a like nature exists.” This regulation implements, in practice, for the U.S. military (or did, until breached by decree of President Bush in 2002), a specific, legitimate source of “law of war” authority under the U.S. Constitution: i.e., Article 5 of the Senate-ratified 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of POWs (Convention III). In the same way, the Uniform Code of Military Justice enacted by Congress – in place of the Articles of War – implements, in practice, many of the other legitimate sources of law-of-nations/“law-of-war” authority that empowers government actors, under the ratified (and thus supreme U.S. law) 1949 Geneva Convention treaties. – pow wow

(Sec. 1033) Prohibits FY2012 DOD funds from being used to transfer any individual detained at Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (Guantanamo) to the custody or control of that individual’s country of origin, other foreign country, or foreign entity unless the Secretary [of Defense] makes a specified certification to Congress, including that the transferee country or entity is not a state sponsor of terrorism or terrorist organization and has agreed to ensure that the individual cannot take action to threaten the United States or its citizens or allies in the future. Prohibits any such transfer if there is a confirmed case of an individual who was transferred to a foreign country and subsequently engaged in terrorist activity. Authorizes the waiver of such prohibition in the national security interest.

(Sec. 1034) Prohibits FY2012 funds from being used to construct or modify any facility in the United States or its territories or possessions to house any individual detained at Guantanamo for purposes of detention or imprisonment by DOD, unless authorized by Congress. Provides an exception.

(Sec. 1035) Directs the Secretary to submit to the defense and intelligence committees procedures for implementing the periodic Guantanamo detainee review process required under Executive Order.

- Which procedures, however, as the enacted law now states in black and white, “shall” “(1) clarify that the purpose of the periodic review process is not to determine the legality of any detainee’s law of war detention, but to make discretionary determinations whether or not a detainee represents a continuing threat to the security of the United States;” (Just possibly because it’s pretty much by definition a war crime – a “grave breach” of the Geneva Conventions – for the U.S. to have shipped non-combatants to Guantanamo…; we begin now to see why a colluding Congress will only discuss these matters behind closed doors.) – pow wow

[See the Implementing Guidelines PDF released in early May, 2012.](Sec. 1036) Directs the Secretary to submit to such committees: (1) procedures for determining the status of [the already-deemed (somehow…, still without benefit of AR 190-8 minimal due process, in open defiance of the unenforced “law of war” language) “unprivileged enemy belligerent“] persons detained pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and (2) any modifications to such procedures.

- “…for purposes of section 1031.” Meaning that this section also covers military prisoners beyond Guantanamo (at our off-shore Devil’s Islands). But see this mile-wide exception that swallows the rule for the entire prison population of Guantanamo, as passed into law in the final version of H.R. 1540 (Section 1024): “(c) Applicability- The Secretary of Defense is not required to apply the procedures required by this section in the case of a person for whom habeas corpus review is available in a Federal court.“ An exception that – thanks to the 2008 Anthony Kennedy-authored Boumediene decision, which belatedly began to police the separation of powers – now encompasses all Guantanamo prisoner “persons.” [If only nominally so, due to the D.C. Circuit’s deliberate undermining of Boumediene’s habeas provisions, in its ongoing effort to replace the presumption of innocence for the accused, with the “presumption of regularity” for the assertions of government-agent accusers.] This Guantanamo exception does not appear to have been included in the version of the law passed by the Senate on December 1, 2011. – pow wow

- (4/22 Update) On April 5, 2012, as Daphne Eviatar of Human Rights First noted in an April 18th analysis, “[T]he Defense Department quietly sent a report to Congress indicating how it intends to implement” this section (Sec. 1024) of the 2012 NDAA, for non-Guantanamo prisoners in U.S. military custody. As Daphne’s post indicates, under the new DOD regulation (and in stark contrast and conflict with still-on-the-books Army Regulation 190-8), the first status determination review by a military judge will be permitted to be postponed for three years after the foreign prisoner comes, unimpeded by lack of lawful due process/review or authority, into U.S. military custody. This military judge “review” is a crude Executive Branch-operated approximation of the ongoing, glacially-slow, government-burden-shifting Guantanamo habeas corpus hearing process in the D.C. District & Circuit federal courts – which was finally instituted and conducted as a mistake-remedying solution years after the established fact of military incarceration of foreigners who’d been denied due process and the law-of-war’s default POW status and treatment. Thus the new DOD NDAA regulation will, in practice, ask a U.S. military judge to decide whether or not he must reverse a decision previously made by a U.S. military commander, and order a foreign citizen released after three years of non-POW detention in a U.S. military prison, in this case because belatedly determined not to be detainable under the terms of Section 1021 of the 2012 NDAA (Sec. 1031 of the Senate bill). [With “international law” and all that jazz, including Third Geneva Convention Article 5’s due process requirements and default POW treatment of military prisoners until a neutral status determination/review is made, having been dispensed with by the U.S. Congress & President (implicitly by the former, explicitly by the latter, beginning with President G.W. Bush).] As Daphne concludes: “The Obama administration had an opportunity to make clear that it takes due process rights and international law seriously [unlike the U.S. Congress], and that, as the war in Afghanistan winds down, it plans to bring indefinite military detention without meaningful review, charge, or trial to an end. It just passed up that opportunity.” – pow wow

(Sec. 1037) Allows a guilty plea as part of a pre-trial agreement in capital offense trials by military commission.

These are the seven incumbent Senators who resisted peer pressure, heeded their consciences, and honored the Constitution by voting No on passage of the above language in S. 1867 on 12/1/2011 (the same seven, joined by six more Senators, also voted No 12/15 on the final Conference Report version):

Tom Coburn (R-OK), Tom Harkin (D-IA), Mike Lee (R-UT), Jeff Merkley (D-OR), Rand Paul (R-KY), Bernie Sanders (I-VT), & Ron Wyden (D-OR).

Having been left to his own devices by his Caucus colleagues, and with oversight of the Armed Services a thing of the past in his committee, Carl Levin’s made the most of it, quickly picking up where he and the Senate left off last spring, in refusing to respect or honor the Constitutionally-mandated process for taking this nation to war. And, before that, in sneaking the Military Commissions Act of 2009 through in the huge FY 2010 Defense Authorization Act (which first passed the Senate, as S. 1391, by a vote of 87-7, and prompted my first FDL reader-diary, in July, 2009, entitled “Senators who lie, Senators who let them”). Two years later, and still the vast majority of incumbent United States Senators, perhaps especially those who share Levin’s Party membership, are incapable of challenging, or are too cowardly to challenge, Levin’s misrepresentations and calculating, back-room sleights-of-hand about domestic and international law – as he, with partners from both Parties, continues to use the power of his legislative office to steadily institutionalize an ever more-powerful, unchecked, and unaccountable presidency.

Very much related to the new, D.C. Circuit-parroting provisions of the 2012 NDAA legislation is the following excerpt (which I trust is within fair use limits, because of the comprehensive length of the original), from an extremely valuable and timely 117-page review of the origins and implementation of the writ of habeas corpus, and its two suspensions, in this nation, which was just published by the Harvard Law Review. It’s an impressive example of the sort of scholarship that should have preceded, but obviously didn’t, the evidently-rushed, end-of-term 2004 Supreme Court opinion in Hamdi (an opinion cited repeatedly by Levin – see below – to justify his NDAA detainee provisions), which makes excellent use of the available accounts of contemporaneous Congressional debates. [Hamdi’s oral argument audio is here; in this diary I transcribed a key portion of that argument.]

With the source(s) of authority being meaningfully enforced at our Guantanamo Bay Naval Station’s prison complex still little more than brute armed force – answering not to law, but to the arbitrary political calculations of one man in the presidency – and with Members of Congress continuing to point to the courts to justify their own trampling of our core rights and liberties, even as federal judges point to Congress for the same purpose – as just re-illustrated in spades by this January 23rd decision of a three-judge Fourth Circuit appellate panel (J. Harvie Wilkinson III, Diana Gribbon Motz, & Allyson K. Duncan), in the case of the American citizen Jose Padilla, who’s been sickeningly abused for years by government agents under color of law – Amanda L. Tyler’s informative new HLR article, “The Forgotten Core Meaning of the Suspension Clause,” dramatically highlights and documents how genuinely unAmerican such actions and decisions are, under our Constitutional system of government.

Tyler (an Associate Professor of Law at George Washington University Law School) – in stark and very welcome contrast to the legislators who hurriedly rubberstamped the 2012 NDAA to get home for the holidays – is one American who’s obviously done a great deal of homework in honorable defense of those cherished human rights that we all want and deserve, but to which only the powerful in America seem to consider themselves entitled today – including especially those in government service grown used to exercising arbitrary power on a whim, in open hostility to the “inconvenience” and “interference,” or even “national security threat” posed by the rights of others.

Compare and contrast (all emphasis added):

Recent Supreme Court jurisprudence, moreover, posits that “‘at the absolute minimum,’ the [Suspension] Clause protects the writ [of habeas corpus] as it existed when the Constitution was drafted and ratified.”9 It follows that ascertaining the Founding conceptions of the privilege and [its] suspension must inform any attempt to make sense of the Suspension Clause today.10

[…]

This Article seeks to unearth the historical evidence that informed the adoption of the Suspension Clause and to discover specifically whether the Founding generation’s understanding of that clause permitted the government to detain without formal charges persons enjoying the full protection of domestic law26 for criminal or national security purposes in the absence of a valid suspension [of the writ of habeas corpus].27 Undertaking this task reveals that the outcome in Hamdi stands entirely at odds with what the Founding generation believed it was prohibiting when it adopted the Suspension Clause. In short, though in the minority in Hamdi, Justices Scalia and Stevens have volumes of history on their side.

[…]

Finally, Part V returns to an exploration of the modern departures from what had otherwise been a consistent view of the constraints built into the Suspension Clause. […] In closing, this Part rejects more generally the idea suggested by the plurality opinion in Hamdi that the guarantees built into the Suspension Clause should be subject to contextual balancing by the courts. To the contrary, all evidence suggests that in recognizing the power to suspend in Article I, Section 9, those who ratified the Constitution provided a specific lever by which the document would become both sensitive and responsive to the needs of national security in times of emergency.

In the end, the historical evidence set forth in this Article — much of which is introduced here for the first time to the debates over the meaning of the Suspension Clause — demonstrates two important lessons. First, many of the questions raised today respecting the government’s power to hold prisoners during wartime are not new. Second, fully anticipating that there would be forceful arguments favoring the recognition of expanded government power to infringe on the liberty of persons within [habeas] protection in times of national crisis, the Founding generation imported the English suspension model into the Constitution as the exclusive means by which the detention of persons within [habeas] protection outside the criminal process for criminal or national security purposes could be brought within the law.32

[…]

The Suspension Clause, Justice Scalia wrote [in dissent in Hamdi], married two ideals central to the inherited English tradition, namely “due process as the right secured, and habeas corpus as the instrument by which due process could be insisted upon by a citizen illegally imprisoned.”92 As he explained:

The gist of the Due Process Clause, as understood at the founding and since, was to force the Government to follow those common-law procedures traditionally deemed necessary before depriving a person of life, liberty, or property. When a citizen was deprived of liberty because of alleged criminal conduct, those procedures typically required committal by a magistrate followed by indictment and trial.93

[…]

Where, as here, the Founders both anticipated a problem — the propensity to favor national security interests over civil liberties in times of emergency — and, in order to address the problem, made an unambiguous decision to adopt a specific and well-entrenched framework, which struck the balance categorically in favor of civil liberties unless and until the political branches made the decision to suspend them, there is an especially powerful case for continuing to honor that choice. Indeed, the review of the historical record that follows demonstrates overwhelmingly that the Founding generation ascribed to the Suspension Clause the same meaning as did the dissent in Hamdi.

[…]

This understanding of treason was important because during the early years of the Republic, charging individuals with the crime of treason — not suspending habeas corpus — was the standard way of proceeding against rebels and other persons who took up arms against the state or were suspected of working with its enemies. There is no evidence, for example, that President Washington considered calling for a suspension to aid his efforts in putting down the Whiskey Rebellion, though he assembled a substantial militia to address the insurrection.485 President John Adams adopted the same course in response to Fries’ Rebellion; like his predecessor, President Adams relied upon the militia and a great show of force to put down the uprising.486 In both cases, when the military sought to accomplish the committal of insurgents, it turned suspects over to civilian authorities for criminal prosecution. There is no evidence that anyone was ever held as an “enemy of the state” or “prisoner of war,” even though both episodes witnessed citizens in armed conflict with government troops.

[…]

[During the 1807 Congressional debates about the Aaron Burr Conspiracy, Representative] James Elliot of Vermont likewise doubted that circumstances warranted “suspend[ing] for a limited time, the privileges attached to the writ of habeas corpus.”535 In his view, these privileges were extensive, for he equated suspension of the privilege with “a temporary prostration of the Constitution itself.”536 Paraphrasing Blackstone, he called habeas corpus “a writ of liberty” and cautioned that its suspension “ought never to be resorted to but in cases of extreme emergency.”537 In his view, suspension was appropriate only when “the existing invasion or rebellion, in our sober judgment, threatens the first principles of the national compact, and the Constitution itself.”538

[…]

Together, the historical evidence from this [1807] period suggests that all understood that without the [formal] suspension [of the writ of habeas corpus], the detention of the citizen conspirators suspected of plotting war on the United States turned entirely on the question [of] whether sufficient evidence existed to sustain criminal charges against them.552 As Chief Judge Cranch wrote at the time:

Never before has this country, since the Revolution, witnessed so gross a violation of personal liberty, as to seize a man without any warrant or lawful authority whatever, and send him two thousand miles by water for his trial out of the district or State in which the crime was committed — and then for the first time to apply for a warrant to arrest him . . . .553

In sum, this historical episode strongly supports the conclusion that “[i]f the Suspension Clause does not guarantee the citizen that he will either be tried or released [in the absence of a suspension] . . . ; it guarantees him very little indeed.”554

[…]

It was not until the Civil War that Congress invoked the suspension authority for the first time. Congress again authorized the President to suspend the privilege during Reconstruction. This second suspension came in response to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the South and its attendant reign of terror. These two episodes constitute the only domestic suspensions in American history ever authorized directly by Congress.556 Both historical episodes are fully consistent with the formal view of the relationship between the privilege and the suspension power that controlled at the Founding.

[…]

The extensive congressional debates leading up to the 1863 Act [legislation that formally authorized President Lincoln to suspend the writ as necessary to defend the Union] also reveal that participants were operating under the assumption that a suspension was constitutionally required for the Executive to detain prisoners during the war outside the criminal process.

[…]

Consistent with the Founding-era understanding of suspension, when these domestic invocations of the suspension power — the only two in American history on the federal level — are viewed together, they demonstrate that the idea of holding a “citizen enemy combatant” on American soil in the absence of a suspension is one without grounding in our constitutional tradition. The two territorial suspensions that followed in the twentieth century likewise support this conclusion.623

[…]

The examples discussed in Part I suggest an increasing modern political and legal acceptance of the idea that wartime conditions justify detaining citizens without charges for national security purposes based on mere suspicion of disloyalty. Consistent with this idea, Congress recently enacted as part of Defense Department

appropriations[authorization (the 2012 NDAA)] legislation provisions that sanction the detention of prisoners, including citizens, for both investigative and preventive reasons as part of the ongoing war on terrorism.635 The new legislation merely codifies existing practices in the war on terrorism and takes the Hamdi Court at its word that “[t]here is no bar to this Nation’s holding one of its own citizens as an enemy combatant.”636

“…and takes the Hamdi Court at its word that…” To wit, here’s an offensive parry by the primary Senate promoters of the 2012 NDAA, that Dick Durbin gamely withstood and singlehandedly rebutted, during some actual Senate floor debate on November 30, 2011; despite the “overwhelming” historical case that Tyler’s review makes on behalf of the position of those opposing these new detainee provisions, somehow similar parries, which take the offensive in the opposite direction, against those trying to undermine our “constitutional tradition” and liberties, remain vanishingly rare in the Senate (not to mention in campaigns for the Senate):

Mr. LEVIN. I wonder if the Senator will yield for a question. Would the Senator agree that the majority opinion in Hamdi said the following:

There is no bar to this Nation’s holding one of its own citizens as an enemy combatant.

Mr. DURBIN. I would respond by saying Justice O’Connor in that decision said:

[A]s critical as the Government’s interest may be in detaining those who actually pose an immediate threat to the national security of the United States during ongoing international conflict, history and common sense teach us that an unchecked system of detention carries the potential to become a means for oppression and abuse of others who do not present that sort of threat. …..

We therefore hold that a citizen-detainee, seeking to challenge his classification as enemy combatant, must receive notification of the factual basis for his classification, and a fair opportunity to rebut the Government’s factual assertions before a neutral decisionmaker.

Mr. LEVIN. Would the Senator agree that specifically referred to there is that a citizen being held as an enemy combatant is–excuse me. Would the Senator agree that what he read refers to the exact statement of the Justice that a citizen who is held as an enemy combatant is entitled to certain rights? Would the Senator agree that that, by its own terms, says that a citizen can be held as an enemy combatant?

Mr. DURBIN. In the particular case of Hamdi, captured in Afghanistan as part of the Taliban.

Mr. LEVIN. She did not say that. She said “a citizen.” I know what the facts of the case are. She did not limit it to the facts of the case.

Mr. DURBIN. I am sorry but she did. The quote:….. individuals who fought against the United States in Afghanistan as part of the Taliban.

Mr. LEVIN. She did not limit it to that. She described the facts of that case.

Mr. DURBIN. She limits it to that case. If I could make one response and then I will give the floor to the Senator. This is clearly an important constitutional question and one where there is real disagreement among the Members on the floor. I think it is one that frankly we should not be taking up in a Defense authorization bill but ought to be considered in a much broader context because it engages us at many levels in terms of constitutional protections.

Mr. LEVIN. I agree with the Senator that Justice O’Connor said what the Senator said she said. Would the Senator agree with me that Justice O’Connor said:

There is no bar to this Nation’s holding one of its own citizens as an enemy combatant.

Would the Senator agree that she said that?

Mr. DURBIN. As it related to Hamdi captured in Afghanistan.

Mr. LEVIN. Would the Senator agree she said that, however?

Mr. DURBIN. As it related to Hamdi, of course.

Mr. LEVIN. I am giving the Senator an exact quote. I know the facts of the case.

Mr. DURBIN. I can read the whole paragraph rather than the sentence.

Mr. LEVIN. You already have. Given the facts of the case. I understand the facts of the case, that it was somebody captured in Afghanistan. My question is, of the Senator: Would he agree that Justice O’Connor said–she is talking about this case, of course—-Mr. DURBIN. Yes.

Mr. LEVIN. “There is no bar to this Nation holding one of its own citizens”?

Mr. DURBIN. Captured on the field of battle in Afghanistan.

Mr. LEVIN. Would the Senator agree that the Justice said the following, that a citizen, no less than an alien, can be “part of or supporting forces hostile to the United States or coalition partners” and “engaged in an armed conflict against the United States,” and would pose the same threat of returning to the front during the ongoing conflict? Would the Senator agree that she said that?

Mr. DURBIN. Of course.

Mr. LEVIN. Would the Senator agree that she quoted from the Quirin case, in which an American citizen was captured on Long Island?

Mr. DURBIN. She did make reference to the Quirin case.

Mr. LEVIN. Did she cite that with approval?

Mr. DURBIN. I would say there was some reservation in citing it. I say to the Senator, our difficulty and disagreement is the fact we are dealing with a specific individual captured on the field of battle in Afghanistan with the Taliban.

Mr. LEVIN. I understand.

Mr. DURBIN. We are not talking about American citizens being arrested and detained within the United States and being held indefinitely without constitutional rights.

Mr. LEVIN. My question, though–my question is: Did Justice O’Connor say that, in Quirin, that one of the detainees alleged that he was a naturalized United States citizen, we held that–these are her exact words:

Citizens who associate themselves with the military arm of the enemy government, and with its aid, guidance and direction enter this country bent on hostile acts, are enemy belligerents within the meaning of ….. the law of war.

Did she say that?

Mr. DURBIN. I can tell the Senator there were references in there to the case, but the Supreme Court has never ruled on the specific matter of law which the Senator continues to read. Until it rules, we will make the decision in this Department of Defense authorization bill, and it is not an affirmation of current law because there has been no ruling.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator from Arizona.

Mr. McCAIN. Isn’t it true that Justice O’Connor was specifically referring to a case of a person who was captured on Long Island? Last I checked, Long Island was part–albeit sometimes regrettably–part of the United States of America.

Mr. LEVIN. She is quoting with approval from the Quirin case in which one of the detainees was—-

Mr. McCAIN. Captured in the United States of America.

Those are the facts of the case.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator from South Carolina.

[…]

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator from South Carolina.

Mr. GRAHAM. Please understand what you are about to do if you pass the Feinstein amendment. You will be saying as a Congress, for the first time in American history, an American citizen who allies himself with an enemy force can no longer be held as an enemy combatant. The In Re Quirin decision was about American citizens aiding Nazi saboteurs, and the Supreme Court held then that they could be held as enemy combatants. So as much respect as I have for Senator Durbin, it has been the law of the United States for decades that an American citizen on our soil who collaborates with the enemy has committed an act of war and will be held under the law of war, not domestic criminal law. That is the law back then. That is the law now.

I interrupt Lindsey Graham here, because such half-truths demand responses, even though, for the most part, none were forthcoming from his Senate colleagues last fall (although I think that Dianne Feinstein, Mark Udall of Colorado, and a few others, including Durbin, deserve credit for at least saying enough to prompt the self-indictment that Graham and Levin, et al, produced through their own words in lengthy public responses to the mild resistance that they did face); so here’s at least one brief retort, published by Eugene Fidell (Professor of Military Law at Yale Law School) on June 13, 2009:

Many Americans have heard of the military commission that convened in 1942 to try eight German saboteurs. But few are aware that a major reason the case was tried by commission rather than in the federal courts was that federal law at the time did not prescribe harsh enough penalties for what they had attempted to do. That is obviously not so today, thanks to the Patriot Act and other [domestic criminal-law] legislation passed since World War II.

In its review of the saboteurs’ case, Ex parte Quirin, the Supreme Court did sustain the military commission’s jurisdiction — but, in a discomfiting move, did not even release its legal reasoning until months after six of the Germans had been electrocuted. Though the ruling was unanimous, Justice Felix Frankfurter declared that Quirin was “not a happy precedent.”

Back to Mr. Graham, who’s steeped in the arrogance of power, and working hard with his doubletalk to create loopholes that will enable the Executive, and pampered public officeholders like himself, to continue to escape the constraints of domestic and international law:

Hamdi said that an American citizen–a noncitizen has a habeas right under law of war detention because this is a war without end. The holding of that case was not that you cannot hold an American citizen, it is that you have a habeas right to go to a Federal judge and the Federal judge will determine whether the military has made a proper case. It has nothing to do with an enemy combatant being held as an American citizen [sic]. What this amendment would do is it would bar the United States in the future from holding an American citizen who decides to associate with al-Qaida.

In World War II it was perfectly proper to hold an American citizen as an enemy combatant who helped the Nazis. But we believe, somehow, in 2011, that is no longer fair.

[…]

Is the homeland the battlefield? You better believe it is the battlefield.

[…]

It is not unfair to make an American citizen account for the fact [a “fact” that will be somehow magically ascertained, apparently, in the absence of due process, before some uncertainly-enforced (if enforced at all) legal niceties will be applied as convenient cover after the fact… – pow wow] that they decided to help al-Qaida to kill us all and hold them as long as it takes to find intelligence [evidently ten years, or more… – pow wow] about what may be coming next. And when they say “I want my lawyer,” you tell them “Shut up. You don’t get a lawyer.”

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator’s time has expired.

Mr. GRAHAM. “You are an enemy combatant [and don’t ask us how we know that, we just do (it’s called the “presumption of regularity” by the D.C. Circuit…) – pow wow], and we are going to talk to you about why you joined al-Qaida.”

[3/30/12 Note: With regard to Mr. Graham’s “Hamdi“-citing, “law-of-war“-sourced claim that “It is not unfair to make an American citizen account for the fact that they decided to help al-Qaida to kill us all and hold them as long as it takes to find intelligence about what may be coming next”, perhaps someone should point out to Mr. Graham (and Senate company) the important Supreme Court statement in the same Hamdi plurality decision that Senator Graham cites, which directly repudiates Graham’s claim of law-of-war detention authority for the purpose of “find[ing] intelligence” – as quoted in a thorough 12/31/11 NDAA Sec. 1021 analysis by Marty Lederman & Steve Vladeck (emphasis added): Moreover, in rebuking a claim put forward by the Solicitor General, [Hamdi author Justice O’Connor] wrote that “[Certainly,] we agree that indefinite detention for the purpose of interrogation is not authorized” [under the 2001 AUMF/law of war], id. at 521—presumably because there was no established predicate for such detention in the laws and practices of war.]

Amanda Tyler again:

With the benefit of knowing the history surrounding the adoption of the Suspension Clause, there is a formidable case to be made that many, if not all, of these [modern] examples stand entirely at odds with the original understanding and underlying purposes informing the adoption of that clause.

[…]

Putting aside the specifics of Hamdi’s case, there is a more fundamental problem with the Hamdi plurality’s approach to the Suspension Clause inquiry. In embracing the idea that pragmatic judicial balancing should play a role in assessing the propriety of wartime detentions outside the criminal process of persons within [habeas] protection, the opinion is entirely at odds with the specific model of suspension that the Founding generation incorporated into the Suspension Clause. By its very design, that clause rejects the idea that where the privilege has not been suspended, the liberty interests that traditionally find enforcement in its remedy could be balanced against governmental interests in preserving national security. Borrowing from one of the speakers in Henry Hart’s Dialogue, relying upon “the remedy of habeas corpus” as “sav[ing] the constitutionality of the prior procedure . . . turns an ultimate safeguard of law into an excuse for its violation.”693 Put another way, championing the role of the privilege as a means of obtaining judicial review at the expense of the specific rights that historically found protection through its enforcement does a disservice to what the Founding generation hoped to achieve in ratifying the Suspension Clause.

[…]

Second, the history reveals that the rules have long been different for persons who fall outside the protection of domestic law. Both English and early American law, for example, viewed persons outside [habeas] protection as enemies in times of war and thereby permitted their preventive detention during ongoing conflict, even without a suspension, in keeping with [that is, in faithful adherence to (remember Army Regulation 190-8?) – pow wow] the law of nations.708 Nothing in the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Boumediene v. Bush709 appears to abandon this traditional distinction, although the majority made a point of highlighting that its “opinion does not address the content of the law that governs” the detention of noncitizens at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, as part of the war on terrorism.710

– Amanda L. Tyler, 124 HARV. L. REV. 901 (2012)

________________________________________________________________

(3/1) See Also: The following descriptions of the undeserved human suffering that’s a direct result of the actions of those in our government – see above – who have been allowed to evade the enforcement of domestic law, in the name of the “law of war” – which has, however, likewise been deliberately evaded and left unenforced (if wartime detainees aren’t detained pursuant to the 3rd Geneva Convention POW treaty – which mandates proper Article 5/AR 190-8 screening – as part of an international armed conflict, then they’re detained pursuant to domestic law and its due process guarantees, not the international law of war…), so far without the slightest consequence for those cloaked in the “national security” excuse for immunity from the requirements of law and basic human decency.

- First, the words of the man for whom Justice Anthony Kennedy, with four of his Supreme Court colleagues in 2008, finally reinstated the (unsuspended) writ of habeas corpus, which brought to an end, in 2009, that man’s “nightmare” (a nightmare that 4 other members of that court were prepared to force this man and his family, and others like them, to continue to endure indefinitely):

My Guantánamo Nightmare

By LAKHDAR BOUMEDIENE

Published: January 7, 2012

Nice, FranceOn Wednesday, America’s detention camp at Guantánamo Bay will have been open for 10 years. For seven of them, I was held there without explanation or charge. During that time my daughters grew up without me. They were toddlers when I was imprisoned, and were never allowed to visit or speak to me by phone. […]

Some American politicians say that people at Guantánamo are terrorists [Lindsey Graham is sure of it, and Carl Levin really can’t be bothered to disagree… – pow wow], but I have never been a terrorist. […]

We were tied up like animals and flown to Guantánamo, the American naval base in Cuba. I arrived on Jan. 20, 2002.

[…] I was kept awake for many days straight. I was forced to remain in painful positions for hours at a time. These are things I do not want to write about; I want only to forget.

I went on a hunger strike for two years because no one would tell me why I was being imprisoned. Twice each day my captors would shove a tube up my nose, down my throat and into my stomach so they could pour food into me. It was excruciating, but I was innocent and so I kept up my protest.

[…]

I will never forget sitting with the four other men in a squalid room at Guantánamo, listening over a fuzzy speaker as Judge Leon read his decision in a Washington courtroom. He implored the government not to appeal his ruling, because “seven years of waiting for our legal system to give them an answer to a question so important is, in my judgment, more than plenty.” I was freed, at last, on May 15, 2009.

[…]

I’m told that my Supreme Court case is now read in law schools. Perhaps one day that will give me satisfaction, but so long as Guantánamo stays open and innocent men remain there, my thoughts will be with those left behind in that place of suffering and injustice.

- Here’s another example – this time from an inmate who was finally freed, not by an American court of law, but by arbitrary Executive will, for reasons as unknown as the reason American government officials jailed him for five years of his life, and brutally mistreated him:

Notes From a Guantánamo Survivor

By MURAT KURNAZ

Published: January 7, 2012

Bremen, GermanyI left Guantánamo Bay [in 2006] much as I had arrived almost five years earlier — shackled hand-to-waist, waist-to-ankles, and ankles to a bolt on the airplane floor. My ears and eyes were goggled, my head hooded, and even though I was the only detainee on the flight this time, I was drugged and guarded by at least 10 soldiers.

[…]

The American officer offered to re-shackle my wrists with a fresh, plastic pair. But the commanding German officer strongly refused: “He has committed no crime; here, he is a free man.”

[…] Strange, I thought, as I stood on the tarmac watching the Germans teach the Americans a basic lesson about the rule of law.

[…] I am not a terrorist. I have never been a member of Al Qaeda or supported them. I don’t even understand their ideas. I am the son of Turkish immigrants who came to Germany in search of work.

[…]

I later learned the United States paid a $3,000 bounty for me.

[…]

I begged the [American] interrogators to please call Germany and find out who I was. During their interrogations, they dunked my head under water and punched me in the stomach; they don’t call this waterboarding but it amounts to the same thing. I was sure I would drown.

[…]

After about two months in Kandahar, I was transferred to Guantánamo. There were more beatings, endless solitary confinement, freezing temperatures and extreme heat, days of forced sleeplessness. The interrogations continued always with the same questions.

[…]

Recently, Mr. Azmy [a volunteer American lawyer assigned to Kurnaz by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) two and a half years into his detention] made public a number of American and German intelligence documents from 2002 to 2004 that showed both countries suspected I was innocent.

- From Cori Crider, legal director at Reprieve, a London-based legal action charity, which represents 15 Guantánamo prisoners and assists many more, writing on February 9, 2012:

I have just arrived in Guantánamo Bay, on my first attorney-client visit [in] a year.

On one level it’s easier to converse with prisoners these days — we have held them so long that many speak American English — but on another, we lawyers have been reduced to little more than glorified pizza-deliverymen to the forgotten and inconvenient.

[…]

Official indifference extends not just to us but to our overall effort to extract their captives. Today, save a scant few slated for military commission — my clients are not — the military pays most prisoners little notice. It simply buses their ‘habeas’ lawyers in and out.

At Gitmo even the word ‘habeas’ is denuded of meaning. […]

[…]

And then maybe, I can say, maybe in thirty years you and your children may receive an official apology. When those who saw in you a scarecrow to keep others afraid and themselves in power are dead, some statesman will come along and tell your family we are sorry; that this was an un-American episode; that these were not our values after all. I just hope these prisoners live to see it.

- Experienced, now-retired Air Force JAG Officer Morris Davis, who resigned on principle in 2007, as chief prosecutor of the Bush-era military commissions, after helping to write (at the invitation of Senators Graham & McCain) part of the 2006 Military Commissions Act – immediately after the Supreme Court had finally exerted itself to the extent of ruling the 11/13/2001 George W. Bush-created commission system unConstitutional, in June, 2006 – in a typically-interesting and informative interview conducted on January 12, 2012:

Morris Davis: Some people find it somewhat ironic that there even is a law of war and that there isn’t a doctrine of “win by any means necessary.” But the laws of war have evolved over hundreds of years. And there are unquestionable benefits to a code of conduct for waging wars that include consequences for not complying with the rules, and particularly for accountability for those in command, which is meant to be applied in a top-down manner.

[…]

We chose Guantanamo a decade ago because some people thought that it was outside the reach of law. And now, we have 171 men stuck in a legal Alice in Wonderland. And so we continue to make bad laws, like the NDAA and the “reformed again and again military commissions” — to continue to try to deal with men we are holding because we took short-cuts and made bad decisions years ago. My hope is that common sense prevails and we can look rationally at the big picture, and we stop trying to make even more bad laws rooted in our prior bad decisions. I hope at some point we remember who we are and what we stand for, we reckon with what we did in the past, and we stop living our lives in fear. I hope we become free and brave again.

(3/3) And:

- The Senate Judiciary Committee decided it might be time to hold the first public hearing in the Senate related to the “Detainee Matters” section of the 2012 NDAA – that 93 Senators had voted to adopt on 12/1/11 (since signed into law on 12/31/11) – and did so, on Wednesday, 2/29/12. Though a full committee hearing, less than half of the committee’s membership of 18 even bothered to put in an appearance, and only 4 of the 7 who did show up (Senators Feinstein, Grassley, Franken, & Lee) meaningfully engaged with the witnesses. The hearing focused on a new piece of legislation co-sponsored by Feinstein & Lee to guarantee Due Process for Americans (the Constitutional guarantees of same evidently being voluntary, in the eyes of many incumbent legislators and federal judges…). To their great credit, Dianne Feinstein (who, unexpectedly, directly challenged ungrounded claims by both Steven Bradbury and Lindsey Graham at key points), Al Franken and Mike Lee all sounded like real Americans during the hearing, and Lee even raised some of the fundamental points highlighted by Amanda Tyler’s new work about the Suspension Clause during his brief opportunity to question panelists.

- The following excerpts are from a powerful Stern Magazine feature on Guantanamo (link is to a PDF version of the German original), which was highlighted and reprinted by Andy Worthington on 2/29, using a translation by Cageprisoners.com:

Guantánamo

By Cornelia Fuchs and Eli Rauss,

Stern Magazine, January 2012[The links below are to photographs of the former detainees, taken since their release, by award-winning photographers Mathias Braschler and Monika Fischer, as published January 11, 2012.]

Story 1: Sami al-Laithi [Imprisoned in Guantanamo from 2001-2005, then transferred to Egypt]

He must have been an impressive lecturer — tall, sharp-witted, of natural authority. A sharp intellect is the only thing that remains for Sami al-Laithi.

He sits slumped in a wheelchair, back and neck in pain with every movement. For six years he has lived in this dark room in his late grandfather’s mansion in al-Gharbia, Egypt. […]

[…] Trapped in a room, he stares at the walls. “The Americans,” he says, “have destroyed me — my health, my soul, my future.”

[…]

The troops broke his back, as they stormed into his cell, with batons and pepper spray, again and again. They kicked al-Laithi, prisoner number 287, with their boots until he could no longer walk. They beat him because he did not want to go into the yard — for him the “humiliation yard.” He refused treatment at the hospital. Torturers, he insisted, could not simultaneously be doctors. They pressed his head between his legs and pulled it back, hard. One of the vertebrae in his neck broke. “I asked why they do these things. Why? No answer,” he says. “For years only the walls listened to me.”

[…]

During his time at Guantánamo, Sami al-Laithi says, he was hardly interrogated at all.

[…]

[…] “Animals would not be treated like this. It is shameful that I should be treated like this, as a part of humanity.”

Story 2: Omar Deghayes [Imprisoned in Guantanamo from 2002-December, 2007]

His right eye is blind, since a guard rubbed pepper spray into it. His nose was broken, his ribs as well. A finger was crushed in the food flap of a cell. He can no longer move it.

[…]

Deghayes, 42, a man of powerful figure, speaks softly: “Every day, every week, they brought me in for questioning, for six years. At the end there was nothing, no charges, nothing.” […]

Nevertheless Deghayes was seen in Guantánamo as “very interesting” — so interesting that Libyan agents were allowed to interrogate him. The men of the dictator Gaddafi threatened Deghayes with torture, when he would be sent to Libya from the US. His father had been murdered there in the 1980s by Gaddafi’s henchmen, and the family fled to Britain. Omar studied law and wanted to be a lawyer like his father.

[…] He liked living in Kabul, in the country of the Taliban: “Life was much slower, much more natural. These beautiful landscapes, nice people.”

[…]

He has accused the government in London of facilitating torture, as British agents knew of his abuse. In an out of court settlement, the [British] government paid him and 15 others an unknown sum. The men may not talk publicly about the sum, which is said to be in the range of millions. Omar uses his share to help the remaining inmates in Guantánamo.

Story 3: Mohammed el-Gharani [Imprisoned in Guantanamo from 2001-2009]He was 16 when he arrived in Guantánamo. He was accused of being part of a terrorist cell in London in 1998, when he was twelve years old.

As one of 63 prisoners to date [to receive a form of habeas due process, from among a one-time prison population of 779 prisoners], el-Gharani’s case was investigated by a judge in the US, who came to the conclusion that the accusations were based almost exclusively on “unreliable witnesses,” and mostly from interrogations in Guantánamo. The judge ordered his immediate release. In fact, it took another six months before he was delivered to Chad.

Although a citizen of the country [Chad], el-Gharani had never lived here. He was born in Saudi Arabia.

[…]

“At my first interrogation, I still thought I might clarify the apparent misunderstanding,” he says. At the second interrogation it was clear: no one was looking for the truth.

[…]

To date el-Gharani has not seen his family in Saudi Arabia. In their cables, US diplomats stated that he should be prevented from traveling. He has not received a passport. […] He is now 24. He spent one-third of his life in Guantánamo.

Story 4: Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef [Imprisoned in Guantanamo from 2002-2005]As the last Taliban ambassador, Mullah Abdul Salam represented the regime in Pakistan. […] His appearances in the limelight of the world press ended in January 2002. Pakistani intelligence officers arrested Zaeef and handed him over to the Americans.

[…]

Among the first ordeals of his captivity was that, amid the laughter of GIs in Peshawar, he had to strip naked, that he was locked in a cage on the warship USS Bataan, that he was tortured in Bagram with mock executions, and attacked in Kandahar by drooling military dogs.

“Guantánamo was different,” says the ex-prisoner number 306. The system there was “aimed at the psyche.” […]

[…] He has been back in Afghanistan since September 11, 2005. ”I was in Kabul for two years under house arrest, with the secret service NDS watching me around the clock,” says Zaeef. However, the longer the war in Afghanistan lasts, the more intense become Western efforts to negotiate with the Taliban. “Diplomats and dignitaries come to my house; President Karzai is talking to me as a consultant,” says Zaeef.

Story 5: Abu Bakker Qassim [Imprisoned in Guantanamo from 2001-2006, then sent to Albania]

The qualified saddler comes from the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in China. He is one of 22 Uighurs who fled from the dictatorship of the communist rule and were sold by bounty hunters in Pakistan to the US military.

[…]

Finally, five of the Uighurs were rehoused in Albania [in 2006], ten on the islands of Bermuda and Palau [in 2009], and two in Switzerland [in 2010]. Five Uighurs are still in custody at Guantánamo [by order of the D.C Circuit Court of Appeals – pow wow].

[…] After he landed in May 2006, in leg irons on Albanian soil, officials drove him to a refugee camp on the outskirts of the capital. […]

[…] The Uighurs cannot find regular work in Albania. Although they have a permit to stay on, they have no passport — and Guantánamo on their CVs.

779 inmates have been held in the prison. Today there are still 171 left. Of these, 89 are cleared for release [by essentially arbitrary presidential decree]. But they remain incarcerated because no state is willing to take them or their home countries are deemed unsafe. The Pentagon says that at least 14 percent of ex-detainees are engaged in terrorism. [Reprieve’s] Stafford Smith disagrees: “The US government has published 44 different [‘recidivism’] lists. And every time they delivered other, contradictory figures. Independent experts were able to verify less than 20 cases by name.”

[…]

In the Bagram military base in Afghanistan alone, the USA has been holding 1500 prisoners without charges [or law-of-war-mandated Article 5/AR 190-8 due process – pow wow], without trial, for years.

[…]

David Hicks, prisoner No. 2

Citizenship: Australian

Duration of captivity: 5 years, 5 months“Guantánamo is eating me from inside.”

Sami al-Laithi, 56, prisoner No. 287 [also above]

Citizenship: Egyptian

Duration of captivity: 3 years, 10 months“My words are not enough to describe what happened to me. They took us completely naked across the tarmac, dogs attacked us. Incredible, such inhumanity.”

Murat Kurnaz, 29, prisoner No. 061

Citizenship: Turkish [but born in Germany]

Duration of captivity: 4 years, 9 months“I was in the American prison in Kandahar for weeks. In the end I would not have objected to simply dying. There was no normal interrogation. They only asked questions while they beat you, kicked you, tortured you with electric shocks.”

Moazzam Begg, 44, prisoner No. 558

Nationality: British

Duration of captivity: 3 years“I understand why the Americans wanted to question people like me after 9/11, a foreigner who had lived in Kabul. I understand that they had to protect themselves. But I will never understand why they held us for so long — in a legal state of emergency and without the opportunity to defend ourselves against the accusations.”

Mohammed el-Gharani, prisoner No. 269 [also above]

Nationality: Chadian

Duration of captivity: 8 years, 6 months“I was only 16. Guantánamo was even worse, for seven years. One night I was about to give up, because they had beaten me four times in one day, sometimes with up to ten men, while they knew that I never was in Afghanistan, that I did not have anything to do with terrorism. They told me so in the interrogations. Now I live in West Africa, where I do not know anyone.”

Omar Deghayes, prisoner No. 727 [also above]

Nationality: Libyan

Duration of captivity: 5 years, 7 months“They should not have treated me like a criminal, which I never was. They beat me up for each word. Once they pinched my fingers in the small flap of the cell door and held it down until the bone broke. They looked at me the whole time. How inhuman do you have to be to look a man into the face while you break his bones?”

(3/10) Finally, three reports about two prisoners who have yet to leave Guantanamo:

- From an important firsthand account – published March 5, 2012 – about the obstacles fashioned by the Executive Branch (aided by the courts) that have helped to give government lawyers the upper hand against the volunteer lawyers who’ve been thanklessly trying for years to help Guantanamo prisoners belatedly obtain genuine due process, in habeas corpus hearings in the D.C. District & D.C. Circuit federal courts:

A Broken Writ, a Kangaroo Court

Habeas corpus rights aren’t intact in America. Just ask my Guantanamo detainee client.

By Leonard C. Goodman

[…]

One of the leading proponents of NDAA, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), assures Americans that habeas corpus will prevent the president from holding people without cause. But Levin should have checked to see what remains of the “great writ” after 10 years of efforts by government lawyers to weaken it in order to justify the indefinite detention of Guantánamo detainees.

[…]

My client, Shawali Khan, is an uneducated Afghan man who grew up on an orchard outside of Kandahar. In 2002, Khan was captured by Afghan warlords and turned over to the Americans. […]

Khan was sent to Gitmo in 2003, based on the word of a single informant. At his habeas hearing in 2010, the government called no witnesses but merely introduced “intelligence reports” indicating that an unidentified Afghan informant had told an unidentified American intelligence officer that Khan was an al-Qaeda-linked insurgent.

Federal appellate courts [that is, D.C. Circuit appellate courts] have ruled in other Guantánamo cases that the government’s evidence must be presumed accurate, thus putting the burden on Khan’s volunteer lawyers to establish that the informant is unreliable. […] But the government said the file was not “reasonably” available. […] But the government refused to declassify the informant’s name.

[…] We demanded to see the note, given that Khan was functionally illiterate. But the note had not been preserved. So we asked to see the “intelligence” report which accused Khan of having the note. But this report had been classified above the security level of Khan’s two attorneys. […] The government lawyers then provided Khan’s attorneys with a “summary” of its secret report. The judge [John Bates of the D.C. District] accepted this summary as sufficient corroboration, and denied Khan’s habeas petition. [A decision that, of course, was upheld by one of the D.C. Circuit’s 3-member panels (Garland, Sentelle, Ginsburg), a year later. – pow wow]

The government’s “summary” of the secret intelligence report describing the missing handwritten note is still classified, but I can report that when, in April 2011, WikiLeaks released Khan’s official Pentagon file, it established that the government’s summary was false.

This past September [2011], we filed a motion demanding Khan’s release based on the fact that the government submitted false evidence to justify his indefinite detention. We await a ruling. Perhaps the judge [John Bates] is struggling to reconcile the rule that says the government is presumed to always tell the truth about suspected terrorists with clear proof that it has lied about Khan.

- From The Independent a month ago, concerning the still-imprisoned Shaker Aamer (who was cleared for release by the Bush administration in 2007, and reportedly also by the Obama administration in 2010, and has a home waiting for him in Britain, yet who not only remains in Cuba, but in solitary confinement – possibly because Aamer reports being savagely beaten on the same June night in 2006 that three other prisoners died at Guantanamo under suspicious circumstances):

Paul Cahalan

Monday, 13 February 2012On the day he marks 10 years locked inside the world’s most notorious prison without having been charged with an offence, the last UK resident in Guantanamo Bay pleads with his captors: “Please torture me in the old way … Here they destroy people mentally and physically without leaving marks.”

Speaking from his cell through letters and comments published for the first time in The Independent today, Shaker Aamer, who has never stood trial, reveals the torment of his captivity and removal from his family. […]

[…] His lawyers are particularly concerned by the deterioration of his mental and physical state, which Mr Aamer describes vividly in his letters. He has lost 40 per cent of his body weight and is suffering from health problems, aggravated by long periods in solitary confinement.

The Independent has seen dozens of handwritten letters from Mr Aamer to his wife and family and today publishes a selection of extracts.

[…]

One of his lawyers, Cori Crider, who visited Mr Aamer in Guantanamo last week [see her related report of that visit above], said: “Shaker has dropped to perhaps 150lb [68kg], his face bears the marks of suffering, and while he has a nigh-irrepressible spirit, the authorities seem determined to grind him down to nothing.”

[…]

Mr Stafford Smith said Mr Aamer began his latest spell in isolation on 15 July last year.

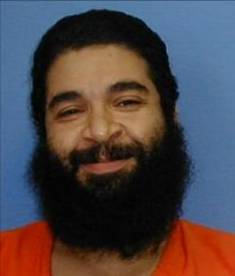

Undated photograph of Shaker Aamer, a Guantanamo prisoner since 2/14/2002, who has been held since 7/15/2011 (until November, 2011, or longer) in solitary confinement in Camp Five Echo

- Andy Worthington elaborates on the appalling, ongoing, supposedly “law of war”-authorized treatment of Shaker Aamer, in a superb account published on February 14, 2012:

Exactly ten years ago today, on February 14, 2002, Shaker Aamer, a British resident, and originally one of 16 British prisoners in Guantánamo, arrived in Camp X-Ray, the rudimentary prison in the grounds of the US naval base in Cuba’s easternmost bay, which was used to hold prisoners until the first blocks of a more permanent facility, Camp Delta, opened for business in May 2002. On the same day, his fourth child, a son, was born.

A hugely charismatic figure, Aamer, born in Saudi Arabia in 1968, had moved to London in 1996, and had worked as an Arabic translator for a firm of solicitors working on immigration cases. He met and married a British woman and was granted residency.

[…]

Instead, however, [Aamer] continues to be held in isolation at Guantánamo, in a block known as “Five Echo,” whose existence was only reported in December [2011], although he managed to play a part in establishing a peaceful three-day protest and hunger strike last month, to mark the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, and to show solidarity with the Americans campaigning to close the prison.

However, in November [2011], one of his attorneys, Clive Stafford Smith, the director of Reprieve, returned from his first visit for many years, and reported that Shaker was suffering from a huge list of physical ailments. In a letter to the British foreign secretary William Hague, urging an independent medical assessment, he wrote, “I do not think it is stretching matters to say that he is gradually dying in Guantánamo Bay.”

In notes from that November visit which were only unclassified by the Pentagon in the last few days, Clive Stafford Smith has only now been able to report that Shaker’s most recent period of isolation began on July 15, 2011. “It is not for doing anything wrong,” Stafford Smith explained, “merely [for] asserting the human rights of his fellow prisoners.”

As Shaker stated, “There is meant to be a 30-day maximum on isolation as a punishment. So it’s not called isolation any more, it’s called ‘separation.'” Stafford Smith added [speaking in 2012], “He is in a cell with no view to the outside, just a one meter by 30 centimetres of opaque glass, and no real toilet, just a hole in the ground [in ‘the most expensive prison on earth‘].”

2 comments

pow wow says:

Tuesday, February 28, 2012 at 9:30 PM EST

The curtain has just risen on DebatingChambers.com.

Greetings, and Welcome, to early visitors who happen by.

Though the post topic is obviously a serious one, this thread is the place to report anything that appears to be haywire on the new site (not much, I hope, since I’ve done my best to thoroughly break-in the site to minimize such problems).

My blogging pace is decidedly less rapid-fire than the norm, so this thread and post will remain open and current for some time.

pow wow says:

Saturday, April 21, 2012 at 12:30 AM EST

The brother-in-law of Shaker Aamer provided us with a revealing update in this March video, in which Aamer’s four children – a 14-year-old girl and three boys, aged 13, 11, & 10 – touchingly plead for their father’s release:

Thouban also quoted these words of Shaker Aamer from their video call in February:

As Aamer’s oldest child and only girl Johina recounts in the March video, her father suffers from asthma, among many other ills, and, as Aamer’s youngest son notes, he’s never seen his father (having been born on the same day his father arrived at Guantanamo), but he thinks of him when he eats and when he sleeps, knowing of the dreadful conditions in which his father is being forced to live in America’s Guantanamo prison camp.

In addition, due to the efforts of one of Shaker Aamer’s attorneys – City University of New York law professor Ramzi Kassem – we know more about the inhumane, sadistic treatment to which Shaker Aamer is still being subjected – a decade into his Guantanamo confinement – even after having been released (probably only because of urgent action taken by Clive Stafford Smith, another of his attorneys, after a November, 2011 visit) from five months of solitary confinement in early December, 2011.

Through newly-declassified notes that Kassem made while visiting Aamer in late January, 2012, Shaker Aamer himself is able to publicly reveal his torment, as exclusively reported by Andy Worthington on April 4th:

As Shaker Aamer further explained to Ramzi Kassem in January, 2012:

This is the supposedly “humane,” supposedly GC Common Article 3-compliant, supposedly “law-of-war”-authorized detention that our Members of Congress boast and brag about, without challenge, and without having bothered – for a decade now – to conduct the slightest degree of meaningful oversight over what goes on behind the wire in Guantanamo.

While Members of Congress, and particularly the Brass Polishers sitting on the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, deliberately look the other way and silently turn their backs on what the DOD is doing to its Guantanamo prisoners, other Americans, and citizens of other nations, are doing what they can to stop the ongoing inhumanity and injustice of the military prisons operated by our Executive Branch of government. Thankfully, Shaker Aamer will be the focus of one such particularly commendable group gathering at The New School in New York this coming Tuesday, April 24th: